News

Nagorno-Karabakh, a fragmented territory that seeks its place in the world

Azerbaijani pressure after the 2020 Armenian military defeat makes tiny country’s position increasingly precarious and largely dependent on Russia · Ukraine’s war does not help prospects for self-determination

The territory, de facto constituted as the Republic of Artsakh, is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan, a dictatorship that allows less freedom than recurrent examples of authoritarian regimes in the region, such as Iran or Afghanistan, but with important economic links to the European Union.

Until two years ago, Karabakh’s was one of several frozen conflicts that emerged during the collapse of the USSR. Internal soviet borders had left Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan, whose fragile autonomy caused conflicts and tensions with the state authorities. In 1988, Karabakh Armenians proclaimed their union with Armenia while the rest of Azerbaijan was rife with pogroms and ethnic cleansing of Armenians. In 1991, Armenian Karabakhis established their independent state, the Republic of Artsakh, after a referendum with 99 per cent in favour and, despite a boycott by the Azeri minority, an 82 per cent turnout.

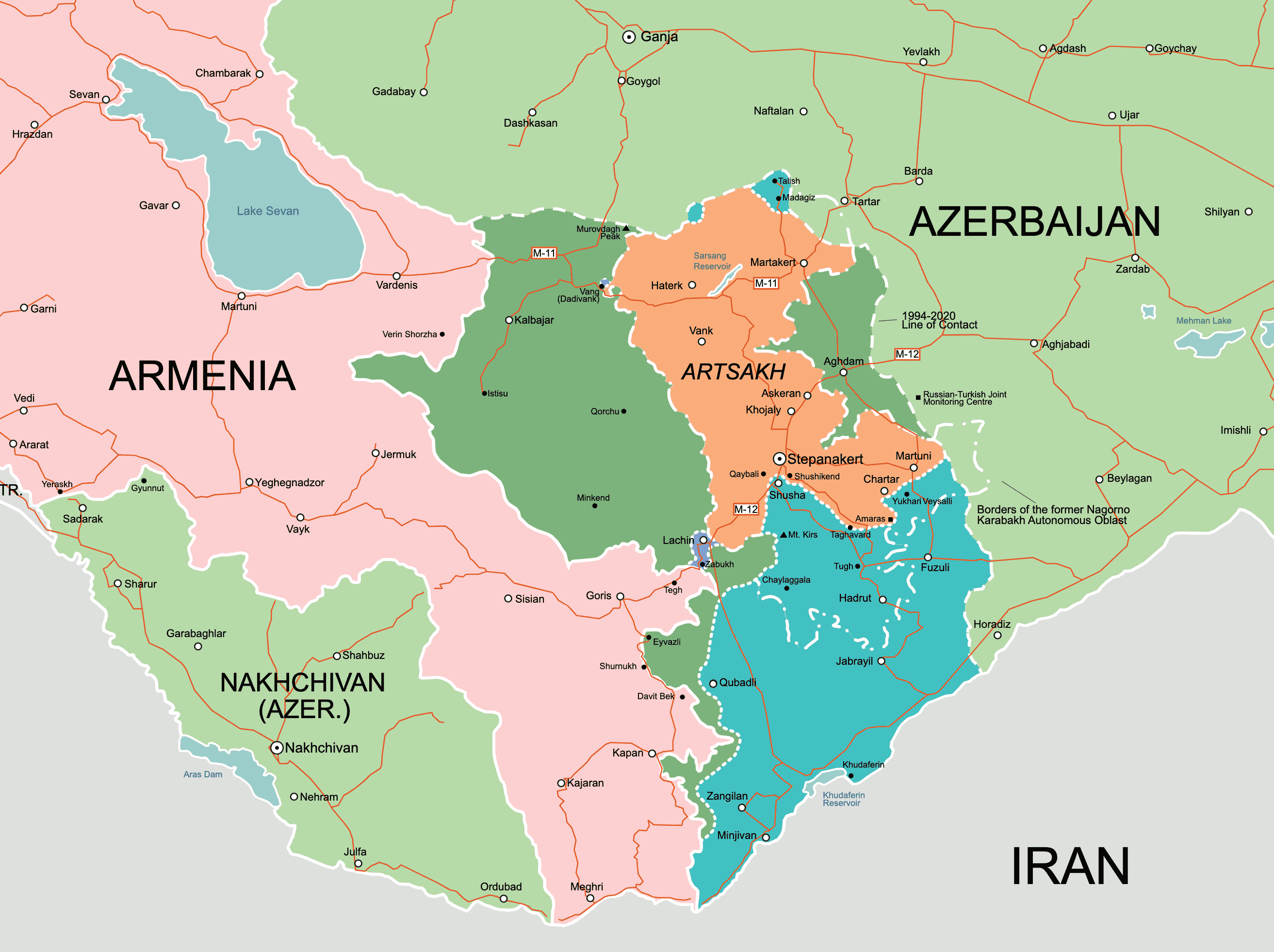

Azerbaijan did not stand idly by and in 1992, with the USSR gone, the war became full-scale, with systematic ethnic cleansing on both sides, close to 1 million displaced people, and some 30,000 dead. Despite having a much smaller population, Armenia was the big winner of the 1994 ceasefire. The Artsakh Republic controlled not only the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, but also the historically Azeri strip separating it from Armenia.

The drone war of 2020

Since then, a precarious ceasefire, signed in 1994 with Russian intervention, had been regularly violated. The Azerbaijani authorities were trying to regain control of the area, without significant changes.

The situation changed radically in 2020. During this time, the balance of power had been shifting in favour of Azerbaijanis, who have three times the population of Armenia, four times its GDP thanks to oil —which accounts for 50 percent of the state budget and 70 percent of exports— and also four times the military spending year after year (in 2021, Azerbaijan’s was 2,703.2 million dollars, while Armenia’s was 619.4 million).

On 27 September 2020, with the world’s population confined by the covid pandemic, on the eve of the US election, and with Armenian-Russian relations at a low ebb after a democratic revolution that had brought Nikol Pashinyan to power, Azerbaijan launched a full-scale military offensive against the Republic of Artsakh, with overwhelming military superiority. The attack was carried out with state-of-the-art weaponry, amassed for the occasion, with nearly a thousand drones targeting tanks, artillery, and air defence systems, along with operational support from Turkey.

The imbalance was obvious, and Armenian knowledge of the terrain or sacrifice was not enough. Moreover, laws of war were disregarded, with hundreds of hectares of forest burned with white phosphorus, indiscriminate shelling, executions, and torture of soldiers and civilians. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that 2,500 jihadist mercenaries had moved into Nagorno-Karabakh via Turkey, while the Turkish and Azerbaijani authorities claimed that Kurdish militiamen were fighting on the Armenian side.

After a 44-day war, the Azerbaijanis seized much of Artsakh’s territory, including the strategic town of Shushi (Shusha in Azeri). In the face of the world’s inaction, Armenia felt compelled to sign an agreement that entailed returning the territories that were not part of historic Nagorno-Karabakh, while keeping a 5-kilometre wide corridor near the town of Lachin connecting the territory to Armenia, and the deployment of 2,000 Russian peacekeepers. The Artsakh Republic lost 75 per cent of the territory it previously controlled.

International affairs analyst Nareg Krouzian explains that Azerbaijan had been preparing for the war for years, with millions of euros invested in modernising the army. The peaceful settlement was not a priority for Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev because “dictators need to distract the local population with nationalist rhetoric.” The Armenian population had so far been unwilling to make any concessions: “Artsakh was a taboo among the population, and any rhetoric regarding any kind of compromise on the issue was shunned.” Nor was it a priority for Russia, as the conflict helps justify the presence of its forces and allows it to secure its southern border. War might therefore seem foreseeable, and the only uncertainty was when.

In orange, territory controlled by the Republic of Artsakh after the 2020 war; in turquoise, territory conquered by Azerbaijan during the conflict; in green, territory returned following the agreement. The Lachin corridor, as of 2022, no longer passes through Lachin / Image: Golden @ Wikipedia

In orange, territory controlled by the Republic of Artsakh after the 2020 war; in turquoise, territory conquered by Azerbaijan during the conflict; in green, territory returned following the agreement. The Lachin corridor, as of 2022, no longer passes through Lachin / Image: Golden @ WikipediaDespite the agreements that stopped the war, with Azerbaijani military superiority being evident, tensions are far from over. In May 2021, Azerbaijani soldiers crossed the border of the Republic of Armenia —they already control 50 square kilometres of Armenian territory—, there have been hundreds of deaths since then, and there still exists the possibility of a new war between the two countries, which would put the very independence of Armenia at risk, with the memory of the 1915 genocide still present.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, the situation is increasingly critical and exceptional. Azerbaijani occupations of villages outside the ceasefire lines are frequent, as are actions preventing the local population from leading a normal life, with gas cuts lasting for days or the blockade of the Lachin corridor.

A peace treaty?

Since the end of the war, negotiations have been held with mediators to reach a peace treaty, with Armenia in a weak position. The main stumbling block is the question of the Republic of Artsakh, an actor that Azerbaijan refuses to recognise.

In the meantime, being in a dire economic situation due to the closure of 84% of its borders, Armenia has also restored diplomatic relations with Turkey —despite the grim memory of the genocide. First, flights between Istanbul and Yerevan were restored; now, cargo flights and the partial opening of border crossings are underway. The last step would be direct trade between the two countries.

Marine Gevorgyan, a professor of History at Yerevan State University who specialises in Armenia-Karabakh relations, says the 2020 offensive is a threat to all Armenians: “The separation between Artsakh and Armenia is artificial!”. According to Gevorgyan, unprotecting Nagorno-Karabakh is a step toward Armenia’s disappearance. The professor recalls that the National Security Council of the Republic of Armenia has long since declared that the only guarantee of Armenia’s security is the resolution of the Karabakh conflict.

On the negotiations, Kourzian says that it is difficult to reach an agreement soon. The analyst finds that the Minsk Group format, under the coordinated mediation of France, Russia, and the US, has failed, and has been replaced by two processes: one led by the EU and the US, and the other by Russia.

Azerbaijan legitimises itself on the inviolability of borders and territorial integrity, while for Armenia, the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh, rather than a territorial dispute, lies in the right of the historical inhabitants to decide their future under the principle of self-determination. A claim that is at a low ebb in international organizations.

Azerbaijan is a preferential partner for the EU: a recent agreement has doubled the Caspian country’s gas shipments to the European bloc. The Azerbaijani government is also known for its so-called caviar diplomacy, a policy based on bribes and gifts to foreign politicians.

Azerbaijan’s demand is now to create a corridor dividing Armenia so that a direct connection between the country, its enclave of Nakhchivan, and Turkey is created —under a rhetoric threat of using force again soon.

Survival in question

The Artsakh Republic now remains in an even more uncertain situation than before, when it was only recognised by Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria, all of them unrecognised states closely linked to Russia. While there is a debate in Karabakh over whether to move towards union with Armenia or rather maintain an independent state —which for decades has been more democratic than Armenia’s—, the 120,000 Armenians remaining there are opposed at all costs to becoming part of Azerbaijan, even under concessions of self-rule. The opposite is true of the Azeris, who see no alternative to full integration of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Both Krouzian and Gevorgyan agree that Armenian security for the time being depends entirely on Russian peacekeepers. However, Armenia does provide socio-economic support to ensure the territory’s viability and functioning, and this year it has transferred there 300 million USD —the largest amount in history.

There is more disagreement over future scenarios. As a historian, Gevorgyan asserts that “the West has never provided any assistance to Armenia’s problems.” In this respect, NATO remained neutral during the 2020 war and called for negotiations. Of the European Union countries, only France got involved and supported Armenia. So Gevorgyan recognises that military —and economic— dependence on an unreliable partner (and one with many other problems) is therefore maintained. The fact that the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (the military alliance around Russia, of which Armenia is a member) has ignored the dispute, and has not intervened in it, has condoned Azerbaijani actions. However, Russia is also not interested in the conflict getting too far out of control and potentially leading to the intervention of Western powers or an irreversible estrangement from Armenia.

For Krouzian, it is highly unlikely that we will see an independent and sovereign Artsakh in the foreseeable future. However, he does envisage two scenarios in which this could happen. One would be Azerbaijan’s democratisation, in which fundamental rights are protected and guaranteed. That, for now, does not appear to be forthcoming. The other would be a Kosovo-style recognition of independence. For that to happen, he says, several geopolitical interests need to be aligned, and Russia should withdraw from the South Caucasus: “The current war in Ukraine has reshaped Eurasia’s geopolitical architecture. With Russia’s gradual weakening, a vacuum is left in the South Caucasus, which is being filled by other regional actors such as the European Union, Iran, and Turkey.” In this case, recognition and the deployment of international peacekeepers would be required.

So, the issue is far from closed: it remains in an extremely fragile situation, and at any moment a flame could be lit that could reignite the conflict.