News

Armenia signs armistice with Azerbaijan, loses two-thirds of Artsakh

Russian peacekeeping forces to be deployed for five years · “We would have lost everything in a matter of days,” says Artsakh president

Armenian political and military authorities —both from Armenia and the Artsakh Republic— explained that they had no choice but to accept the ceasefire agreement, as it was the only option if the Armenian presence in Nagorno-Karabakh was not to be liquidated over the coming weeks, in view of the far superior Azerbaijani military air power.

“We would have lost all of Artsakh in a matter of days,” said Artsakh President Arayik Harutyunyan in a recorded message, “and we would have had many more casualties.” Armenian forces have acknowledged the loss of at least 1,300 lives.

On the Azerbaijani side no figures have been given, but several analysts agree that the number must be even higher than the Armenian one.

War began on 27 September 2020 after Azerbaijani forces launched an offensive against Artsakh, with military support from Turkey. The Azerbaijani army gradually occupied territories in Artsakh, especially in the south. In recent days, Azerbaijani forces reached the centre of Nagorno-Karabakh, where they occupied the city of Shushi, a few kilometres from the Artsakhian capital Stepanakert.

What does the agreement provide for?

The ceasefire agreement was signed by the president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev; the prime minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinian; and the president of Russia, Vladimir Putin. It envisages a ceasefire and cessation of hostilities from 10 November, as well as the exchange of prisoners.

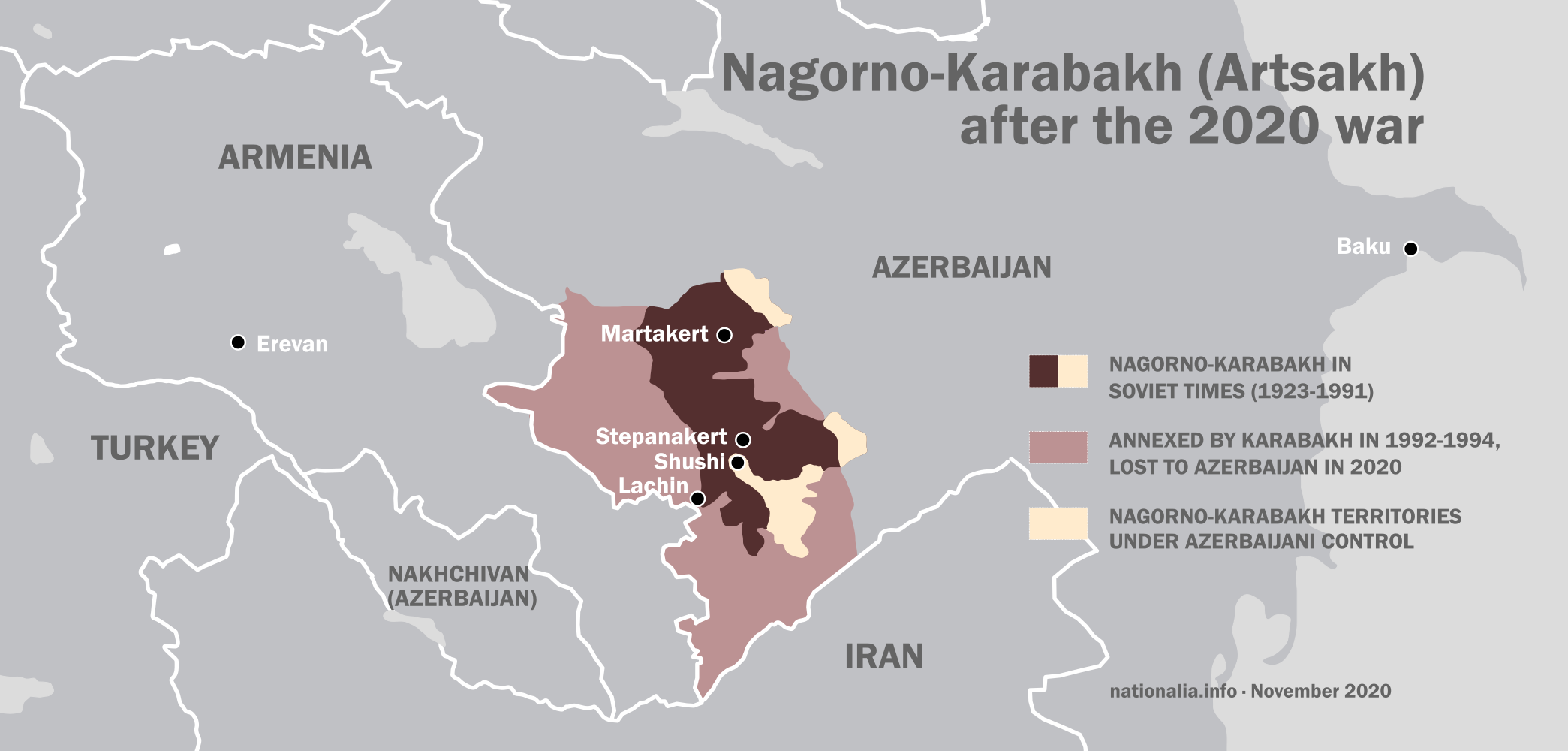

The Armenian forces undertake to leave all the Azerbaijani territories around Nagorno-Karabakh proper —that is, in accordance with Soviet-era borders— until 1 December. Azerbaijan will keep control of the territories it has conquered within Nagorno-Karabakh proper, including the town of Shushi (Shusha in Azeri).

The Armenian withdrawal approximately amounts to the loss of two-thirds of the territories that hitherto constituted the Republic of Artsakh, which consisted of Nagorno-Karabakh proper plus its surrounding districts. Nagorno-Karabakh will now be left with an area of just under 4,000 square kilometres, whereas it previously controlled 11,400.

From today a contingent of 1,960 Russian troops is being deployed to the front as peacekeepers. The contingent will also control a 5-kilometre-wide corridor in Lachin, which will connect Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh. Over the next three years, a new road will be built through this corridor to facilitate transit between both Armenian territories.

The presence of Russian soldiers is planned to last for five years, with automatic extensions for successive five-year periods, provided neither side requests the end of such provision.

The return of refugees and IDPs is permitted in Nagorno-Karabakh and the adjacent territories, in a process to be controlled by the UNHCR.

Armenia undertakes, under Russian supervision, to “ensure the security” of a transport corridor between the Azerbaijani enclave of Nakhchivan and the rest of Azerbaijan. The corridor will allow for the first time a direct connection between Turkey and the whole of Azerbaijan, crossing Armenian territory.

What does it not provide for?

Nowhere is there any mention of a special status for Nagorno-Karabakh. In fact, Aliyev, in his first televised appearance after the signing of the agreement, boasted that the document does not include it. Armenia has simply negotiated the maintenance of the territory —shrunk, as explained before—for five years.

Nor do the authorities of the Republic of Artsakh, which are completely dependent on Armenia in the military field, appear in the agreement. Artsakh President Arayik Harutyunyan said that the signing of the armistice was “unavoidable.”

Will it be possible to rebuild Artsakh?

To begin with, it is difficult to imagine that what is left of the Artsakh Republic —if anything— will be able to function normally again.

A fundamental aspect of this is that most of the Armenian population —over 100,000 people— have fled Artsakh. It is reasonable to wonder whether these people will wish to return, bearing in mind that in five years’ time Azerbaijan may unilaterally denounce Russia’s presence in the territory, and complete the military conquest.

If Artsakh has already needed Armenia’s assistance in several respects over the years, it is likely that it needs it now even more, taking into consideration the physical destruction the war has brought about. Infrastructures and homes have been damaged, and some people will not be able to return to where they previously lived because those territories will be left in Azerbaijan’s hands.

In geopolitical terms, Artsakh —and, more generally speaking, Armenia— will now be even more dependent on Russia.