News

Appetite grows for Welsh independence amid pandemic, Brexit

A very strong identity, but somewhat fragile too

The history of Wales has for centuries been closely linked —and often subordinated— to England’s. Wales was conquered in the 13th century by English king Edward I. In 1535 and 1542, through the Laws in Wales Acts, it was fully assimilated into the English system. However, its own language and culture survived, and a strong Welsh identity was kept.

According to the last census (2011), 57.5% of the Welsh people identify as “Welsh only” while a further 7.1% say they have both Welsh and British identities. The feeling of exclusively belonging to Wales is undoubtedly strong —even stronger than that of Catalans or Basques—, but at the same time, signs of great fragility are shown, since around a third of the population declare no Welsh feeling at all.

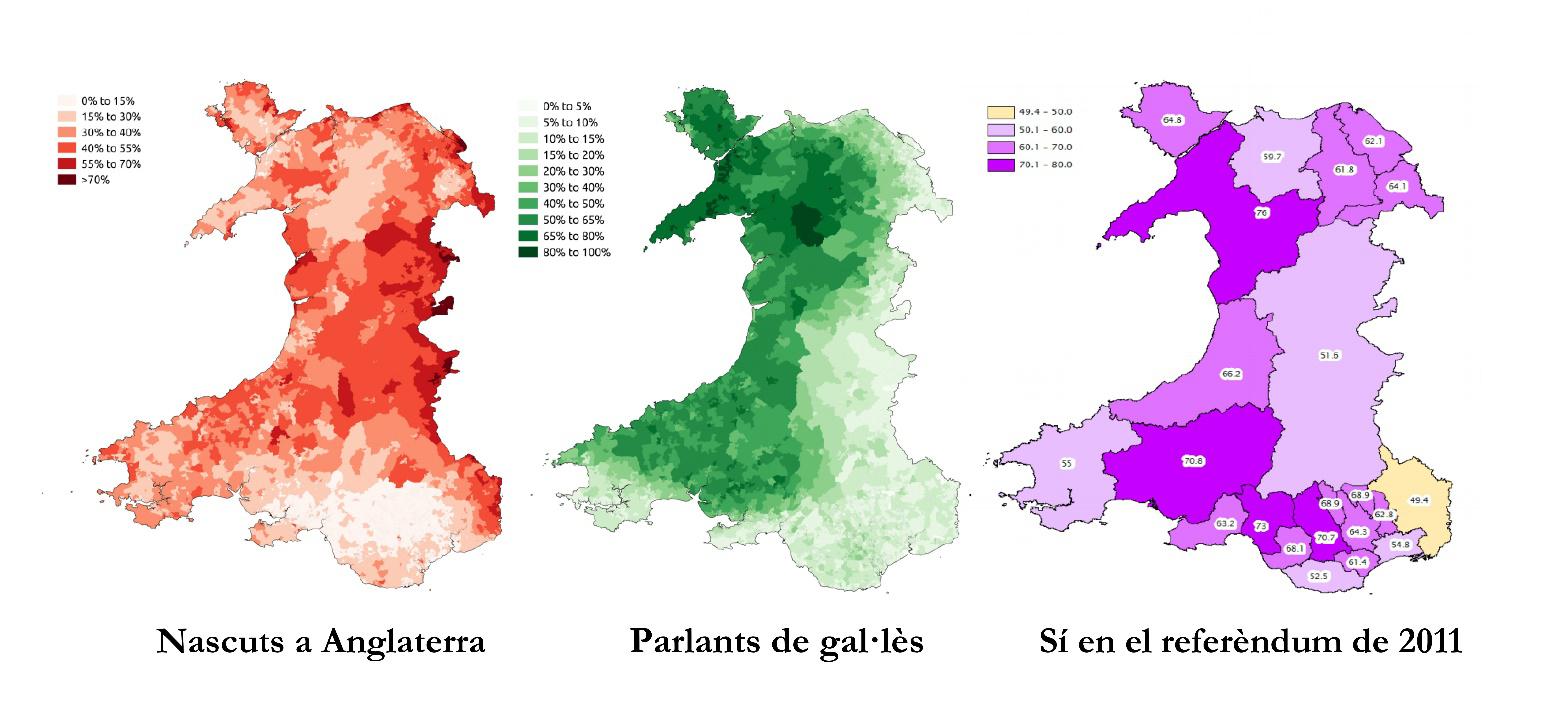

This is largely explained by the fact that 1 in 5 Welsh people —636,000 inhabitants— are born in England, a significant proportion of whom feel English or British. Territorial disproportion can also be mentioned: for instance, in the border county of Powys, 45% of the population is born in England. In the county of Flintshire, close to Liverpool, 44% are born in England, and 32% feel British. In fact, if we look only at those born in Wales, 80% feel only Welsh.

Share of people born in England (left), of Welsh speakers (centre, 2011 census) and results of the 2011 referendum on enlarged devolution (right) / Image: SkateTier (left and centre) and Senedd Cymru (right).

Share of people born in England (left), of Welsh speakers (centre, 2011 census) and results of the 2011 referendum on enlarged devolution (right) / Image: SkateTier (left and centre) and Senedd Cymru (right).In this regard, political analyst Dennis Balsom proposed in 1985 a “three Wales” model, which is still taken today as a reference, if only for the sake of argument.

Broadly speaking, the north-western part of the country coincides with what this model calls “Y Fro Gymraeg” (“The country/area of the Welsh language”), where Welsh is in widespread use, with a strong sense of belonging, and where the pro-independence Plaid Cymru party dominates. The valleys in the south of the country are the so-called “Welsh Wales”, also with a strong Welsh identity but with Labour domination and a much smaller presence of the Welsh language. The rest, mainly the areas bordering England, are the “British Wales”, with a weaker identity and where Liberals and Conservatives tend to dominate.

As for Welsh, it should be borne in mind that already one hundred years ago the process of language shift to English was advanced. Welsh was already residual in many areas, only spoken by 43.5% of the total population. Over the following decades, it continued to decline. However, immersive schools, an improved social prestige, and institutional protection have reversed the trend. Now, 3 in 10 Welsh speakers are aged 15 or younger.

The road towards self-government

Wales’s national survival is largely explained by two reforms that took place from the 18th century onwards. The revival of Welsh Methodism, separate from the Anglican church, sustained the language in rural areas at a time when it was excluded from any other area of public life. Moreover, the widespread and early industrial revolution quickly consolidated a strong labour movement.

Professor of Welsh Politics Richard Wyn Jones of Cardiff University explains that this shaped Welsh politics. The Liberals quickly gained a majority support: they had as their social base this non-conformist religious movement and the working class, which tended to speak Welsh and still maintained a Welsh (combined with British) identity. In contrast, the Conservatives drew support from a smaller, Anglican, Anglicised middle class for whom Welsh identity meant little or nothing. Such a division still today creates dynamics that result in the fact that the Conservatives, despite having been dominant for a long time in England, have not won any major election in Wales since 1859.

It is against this background that Cymru Fydd, a liberal society that sought to create Welsh national consciousness and achieve self-government for Wales, was established in 1886. Among its leaders was David Lloyd George, the only UK prime minister to date to have had Welsh as his or her mother tongue. In the following decades, with a similar social base, the Liberals were replaced by Labour, allowing that social democratic party to dominate Welsh politics for a century.

As an alternative between the two blocs, in 1925 the Plaid Cymru was born. Currently the main pro-independence party, due to Labour’s strong dominance it was not able to consolidate its electoral performance until the second half of the 20th century, when Welsh nationalist demands became stronger. In the early 1970s the Welsh Language Society, or Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg, was established as a lobby group. In 1966, Plaid Cymru made it into the UK Parliament for the first time.

In such a context of cultural resurgence, the disappearance of the rural community of Capel Celyn was a turning point for those supporting Welsh self-government. Despite it being one of the last Welsh-speaking communities in its region, the village was evacuated in order to make room for a reservoir supplying water to Liverpool’s factories, even if the measure had been opposed by local authorities and 35 of 36 Welsh MPs. These events sparked much unrest among the population.

However, a few years later, in the 1979 referendum, only 20% of the Welsh people voted for an assembly of their own. There were several reasons for this. As Siôn Jobbins, chairman of pro-independence civil society group Yes Cymru, explains, on the one hand basic concepts such as nationhood and what it entails (language, nationality, institutions) were not mature enough in Wales. On the other, the political context was not ideal either, with Labour —which had pushed for the referendum— being hit by internal division and at a low ebb in the context of the Winter of Discontent of 1978-79, a disorganised “yes” campaign, and a proposed assembly without primary legislative powers that did not appeal even to Welsh nationalists.

The following decades saw Wales radically transform itself. In 1997, a narrow majority of 50.3 per cent supported self-government in a new referendum. The situation had now changed, with 18 consecutive years of Conservative governments in the UK, a new consensus on previously divisive issues —such as the language—, and an alliance of Welsh Nationalists, Labour and Liberal Democrats, all as one, recognising Wales as a political nation.

Moreover, the fact that different levels of government already existed by the time, thanks to the integration into the European Union, meant that devolution was not seen as a step towards the disintegration of the United Kingdom. According to Professor Richard Wyn Jones, the change in Labour’s attitude was key, as the party was electorally hegemonic. A new generation of leaders stood for culture, language, and a decentralised model of government, and were unashamedly defining their own national profile.

The road towards independence

Since devolution was approved by the UK Parliament in 1998, Labour has consistently led the Welsh government. Confidence in self-government has grown among the population: indeed, in the 2011 referendum on whether the Assembly should get more powers, “yes” comfortably won, with 63.5 per cent of the votes.

Over the last decade, a section of the population has moved towards pro-independence stances. Especially in the wake of Brexit and the pandemic, Wales has entered a new political reality. There is now broad consensus that the Welsh government has handled the coronavirus crisis better than the UK government. Amid the Brexit context, many have made a simple reflection: if UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson says that we must leave Europe in order to “control our laws and our national destiny,” why should be Wales managed from London —where much less knowledge of the Welsh reality exists— and not from Wales itself?

As Professor Anwen Elias of Aberystwyth University argues, the growth in support for independence appears to be a response to the growing perception that the way Wales is governed from London is not appropriate. However, the fact that the unity of the United Kingdom is more contested than ever has also meant that those in favour of abolishing the Welsh Parliament have increased in numbers, which has led to further questioning of Wales’s current constitutional status at the other end of the spectrum.

The birth of Yes Cymru, which has been successful in growing from 2,000 members in early 2020 to over 17,000 now, has shaken Welsh politics. The group’s chairman, Siôn Jobbins, says that “what has helped accelerate Yes Cymru’s growth is the fact that people have seen that the Senedd [Welsh Parliament] is much more able to manage Welsh affairs than Westminster is.”

The ability to bring people who have never voted Plaid Cymru closer to pro-independence stances has been key to the change. As Professor Richard Wyn Jones explains, one of the interesting things about Yes Cymru is that it also appeals to those who do not speak Welsh. Siôn Jobbins says that the group is inspired by Scotland’s 2014 “yes” campaign, which focused on organisational or model aspects, not so much on history and culture: it tries to appeal to people from all parties and backgrounds, even if this means prioritising English on some occasions.

The mobilisation of civil society has also led to the first independence demonstration in the history of Wales, on 11 May 2019, which brought together 3,500 people in Cardiff. It was called by AUOB Cymru (All Under One Banner Wales), a campaign bringing together all supporters of independence, also mirroring its Scottish counterpart. The pro-independence campaign is now more uninhibited and active than ever. Last year, the Welsh Parliament debated a motion for a referendum, and dozens of municipalities have passed pro-independence motions.

Plaid Cymru, although it has not attracted all of the new pro-independence voters, has also achieved landmark results. In the last European election, the party outperformed Labour for the first time in its 94-year history to become the leading party among those supporting remaining in the EU. As Professor Anwen Elias explains, the party had over time had a programme emphasising the protection and promotion of Welsh language, which was particularly attractive in Welsh-speaking regions, which are the party’s core areas. However, over the last few decades it has broadened its discourse to focus on other issues, such as economic and sustainable development, which has made the party more attractive in areas where Welsh is not as widespread.

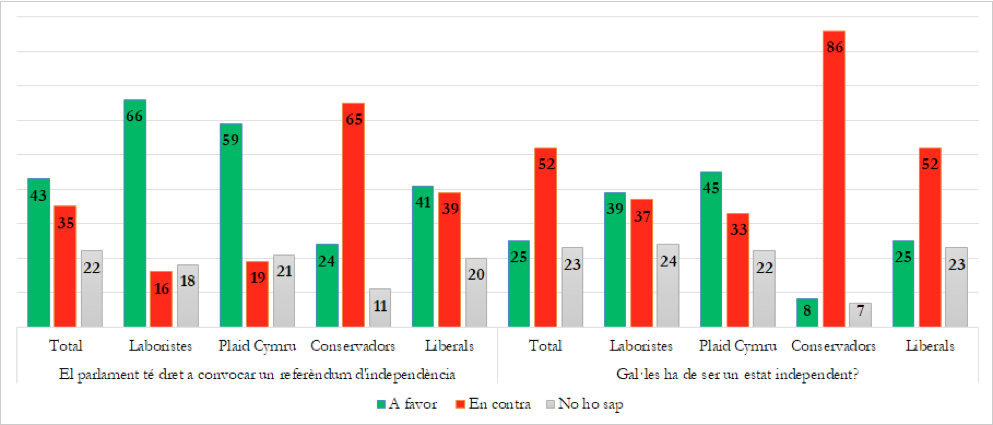

Attitudes on whether the Welsh Parliament has the right to call a referendum (left) and on whether Wales should become an independent country (right). / Image: Àlex Solano and Seda Hakobyan on YouGov data, August, 2020, according to vote in 2019 UK election vote.

Attitudes on whether the Welsh Parliament has the right to call a referendum (left) and on whether Wales should become an independent country (right). / Image: Àlex Solano and Seda Hakobyan on YouGov data, August, 2020, according to vote in 2019 UK election vote.There is now a majority of Welsh people who believe that Wales has the right to hold a referendum if the Welsh Parliament so decides, including a significant proportion of Labour and Liberal Democratic voters. However, those supporting independence are still in the minority.

As Professor Anwen Elias explains, a feature of Welsh politics is that Plaid Cymru is not the only party that appeals to people who regard themselves as “Welsh only”, especially after the creation of the Welsh Assembly. Labour has de facto become a national party, which translates into a commitment to language and culture, as well as to strong self-government. This leads many people who identify themselves as Welsh to support further devolution rather than outright independence.

More than Plaid Cymru’s growth, the rise of support for independence among Labour voters —still the dominant party in Wales— may be now the key. This is unprecedented, and it is uncertain how it will evolve and what it might mean in the long term.

What now?

The constitutional debate in Wales has accelerated very quickly, in just a few years. Plaid Cymru only formally adopted the goal of independence in 2003, and it has only been in the last two years that the issue has been put on the table. Welsh nationalism had traditionally been about nation-building rather than seeking independence, because Wales needed first and foremost to be endowed with self-government.

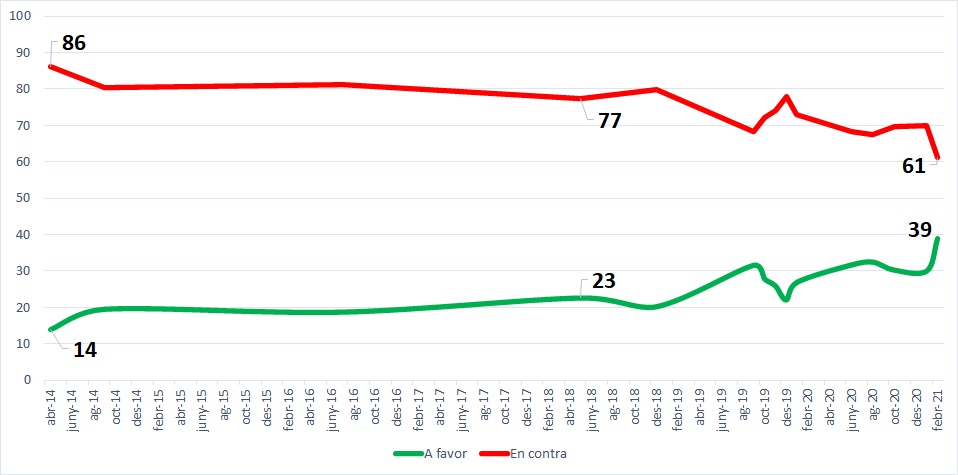

Whereas a few years ago only 10 per cent of the population supported independence, a much commented January poll showed that 31 per cent are now in favour of it —once undecided voters are excluded— and 40 per cent support a referendum within the next five years. Support is especially high among young people, whose identity is more detached from the UK and of whom a majority would vote “yes”. A more recent survey has put support for independence even higher, at 39 per cent, undecided voters excluded.

Evolution of preference in Wales on independence (green line: supports; red line: opposes). / Image: compiled by authors.

Evolution of preference in Wales on independence (green line: supports; red line: opposes). / Image: compiled by authors. The scenario that now opens up has already put the referendum on the horizon. Plaid Cymru, in the run-up to the 6 May 2021 Welsh election, has included in its manifesto a commitment to hold a referendum before 2026 if it is able to garner enough support for it in the Senedd. At the moment, this seems unlikely.

Beyond the independence proposal, the Abolish the Welsh Assembly Party seems set to win about 5 of the 60 seats at stake. Amid this debate, voices are rising at the UK level calling for reforms to accommodate the constituent nations as a whole. Former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown has called for a move towards a federal framework, as the nations and regions, he believes, are often treated by the centre as if they were “invisible”. Otherwise, Brown warns, the current situation could lead to the end of the UK. Labour leader Keir Starmer has also argued for a federal model, as have the Liberal Democrats.

Perhaps reforms will be implemented and the situation will be put back on track. However, it may also happen that in the next few years Scotland will become independent and Northern Ireland will be reunited with the Republic of Ireland. In this scenario, Siôn Jobbins believes that a Welsh referendum would be almost inevitable in 5 to 10 years’ time, where either the “yes” vote wins or Wales is de facto incorporated into England. How the UK will evolve is still unknown, and it will shape what happens to Wales. In the meantime, the independence movement continues to grow.