Opinion

The Sahel, the territory Hegel did not consider

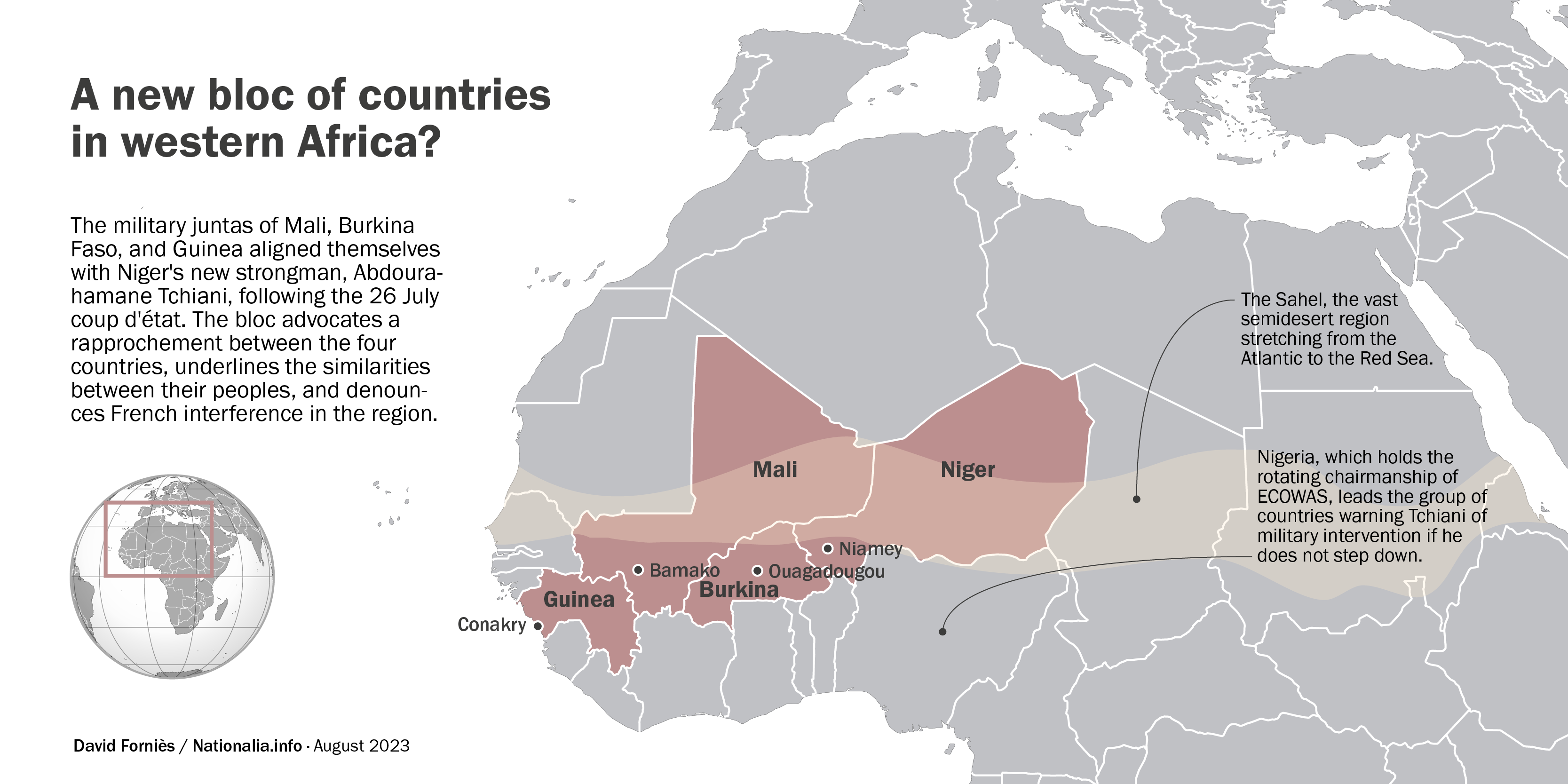

The coup d'état in Niger on 26 July has left West Africa divided between the countries that support the military junta —Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea— and those that have publicly said they would assist a military intervention in the country to return the elected president, Mohamed Bazoum, to power in 2021, which are Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Senegal. Other countries making up the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) —Gambia, Cape Verde, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Togo— have not made statements on the matter.

The countries of the bloc in solidarity with Niger are also led by military juntas that came to power through a coup d’état. In 2021, both Assimi Goïta in Mali and Mamadi Doumbouya in Guinea assumed the presidency of their country. In 2022, Ibrahim Traoré did so in Burkina Faso. All three, career military officers, organised the mutiny under different organisations of which they have become presidents: in Guinea, the Comité National du Rassemblement pour le Développement (CNRD); in Mali, the Comité National pour le Salut du Peuple (CNSP); and in Burkina Faso, the Mouvement Patriotique pour la Sauvegarde et la Restauration (MPSR). Now, in Niger, the military junta has organised itself under the name Conseil National Pour la Sauvegarde de la Patrie (CNSP).

The four coups have also had an anti-colonial character, distancing the countries from former imperial power France and the so-called “Françafrique”: the cultural, political, and economic influence the latter has maintained over these African countries since their independence in the early 1960s. Thus, this new bloc, located in the central Sahel, marks a historic shift in sovereign countries opening up to the world beyond their colonial ties.

As historian Idrissa Rahmane explains, “Western observers were stunned by the news that the country's [Niger] status as the Last Man Standing in the Sahel, a model of stability and democracy in Western diplomats' imagination, was escalating.” Indeed, the historian himself notes in this article that the Sahel has always been described and seen from the West as “a land somewhere on the continent that Hegel banished from history.” The Sahel is a semidesert strip that crosses the African continent from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. It cannot be that there is nothing here, least of all history.

Brotherly peoples

Following a council of ministers in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, in February this year, Malian Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maïga and his Burkinabè counterpart, Apollinaire Kyelem de Tambèla, announced the idea of creating a federation between the two countries to fight terrorism and address humanitarian issues. “The peoples are already federated; it is administrative artificiality and politics that separate us,” said Kyelem de Tambèla.

From the 15th to the end of the 16th century, parts of present-day Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger were part of the Songhai Empire, one of the great Islamic empires. The Songhai Empire followed the Niger River and had its capital at Gao in present-day Mali. Songhai succeeded the Mali Empire, led by one of the richest men in history, Emperor Mansa Musa. Neither the Songhai nor the Mandinka people (of the Muslim Mali Empire) conquered more territory, as the Mossi kingdom (in present-day Burkina Faso) fought against them. This history of links and separations helps explain why, today, within the same country like Burkina Faso, there are people who speak Dyula —a Manding variety— or Mooré —the language of the Mossi people— who do not understand each other, while some Burkinabè can understand a person from Mali who speaks Bambara because this language is part of the Manding family.

For both ministers, therefore, recovering historical memory is also part of the anti-colonial discourse and of reclaiming Africa's position in history, which the West has been busy dismantling. Because understanding that the Mali Empire has been one of the richest and most powerful in the world demolishes the idea that Africa has always been poor: it is this kind of discourse that both Burkina Faso and Mali have recently focused on.

Military front

The need to transcend colonial borders is also due to the failure of UN security programmes and EU and French leadership to halt jihadist terrorism in the Sahel. Since the deployment of Operation Barkhane in Mali in 2015 —where France sent 5,000 soldiers— or the G5-Sahel military coordination force, which was launched in 2014, MINUSMA soldiers and all operations, security and peacekeeping programmes in the region have had no positive results, quite the contrary. From 2015 to the present, terrorism deaths and attacks have only increased. Moreover, terrorist groups have gained territory and have established a foothold in societies. The most affected area, beyond state control, is precisely the one around the triple border connecting Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Mali and Burkina Faso have already launched joint military operations in their border territories. Several media reports suggest that former head of the Nigerien army Salif Mody had travelled to Bamako to negotiate security measures. An adventure that Bazoum, an ally of the West, did not tolerate: he sent Mody as ambassador to the United Arab Emirates in April 2023. It is also rumoured that Bazoum sought to dismiss the head of his own presidential guard, Abdourahamane Tchiani, the general who led the coup in Niger and now heads the country. It is too early to know what the motives were. What is clear is that Tchiani has, in a very short time, followed in the footsteps of Ouagadougou and Bamako. One example is the statement affirming the suspension of military agreements with France. Tchiani has given French troops deployed on Nigerian territory between one and three months to leave the country.

Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger’s GDPs total $53.8 billion. This is far below the GDP of Nigeria, West Africa’s largest power, which totals $440.8 billion. The three Sahelian countries have a very low population density, but are home to 68 million people. These countries rank lowest on the Human Development Index. Despite receiving millions of euros in development aid since independence, they have not seen living conditions improve.

Even as the military juntas in Mali and Burkina Faso seek to break all ties with the former metropole, they still have a lot of work to do economically. On the one hand, all three countries are dependent on the CFA franc —which originally stood for “French Colonies of Africa”— a colonial currency linked to the euro and which obliges countries to inject half of their foreign exchange into the Bank of France. On the other hand, large multinationals and companies such as Orange (a telecommunications company) are owned by French capital. Without a short-term solution, initiatives such as the creation of a community entrepreneurship programme through popular shareholding in Burkina Faso to generate its own food industry and thus become less dependent on imports are worth highlighting. Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the transitional president of Burkina Faso, unveiled the project in June: “It involves making the people the owners of capital and labour,” he said.

Inter-community conflicts

Beyond the terrorist fighting and the military junta policies, each country has intercommunal tensions, but there is a specific one that runs throughout the Sahel. The Fula people (also known as Fulani, or Fulbe), widely dispersed throughout central Sahel, and of nomadic or semi-nomadic tradition, have over the centuries engaged in cattle-raising and were among the first to practice Islam in West Africa. For a time they controlled trade in the Sahel, as they knew the routes through this semidesert area, and established empires, emirates and caliphates there. However, with the arrival of European settlers, agriculture and sedentary lifestyles were promoted. This is why the capitals of these three states —Bamako, Niamey, and Ouagadougou— lie just below the Sahelian strip. The creation of centralised states privileged some peoples, who gained the most power, over others, such as the Fula. Today, the Fula are stigmatised, as they are directly associated with terrorism. According to Spanish newspaper El País, 10,000 Fula community members have disappeared or been killed since 2015 in Mali and Burkina Faso.

The coup d’état in Niger has not only shown that the Sahel is not a region without history, but is writing it anew.