News

When Kamira Nait Sid disappeared under a gas cloud

Amazigh activist embodies struggle of a people brutally repressed by the Algerian regime and ignored by a Europe that has more immediate priorities than human rights

“In due course I had told the council that we needed someone with dual nationality, with an extra passport with which to move freely and which could offer protection in a case like this,” recalls Fathi Ben Khalifa, a well-known Amazigh activist from Libya who took over the leadership of the World Amazigh Congress on the occasion of the war in Libya in 2011. He was succeeded by Nait Sid in 2015.

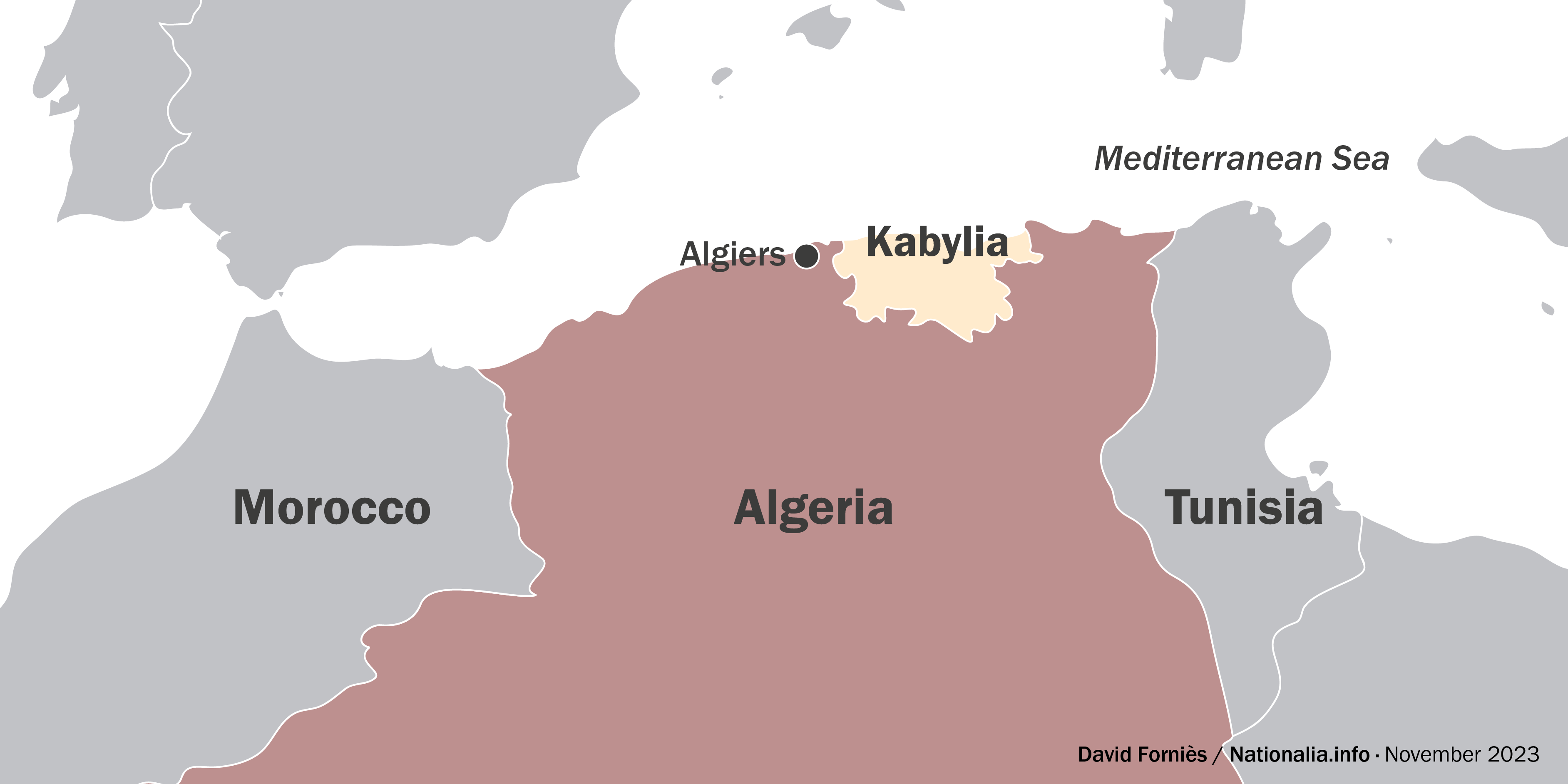

Ben Khalifa highlights the respect enjoyed by the Kabyles among the wider Amazigh community. He describes a people “very active in defending their rights and their language,” as well as a “symbol of resistance against dictatorial regimes” as evidenced, he says, by the existence of the Provisional Government of Kabylia in Exile established in Paris in 2010.

With two episodes as recent as they are eloquent, Ben Khalifa illustrates the current situation of Algeria’s Amazighs. Algiers formally requested that Tripoli outlaw Libya’s Amazigh Supreme Council last spring. Shortly afterwards, a children’s football team from Jadu (Libya) travelled to Algeria to take part in a football tournament.

“The organisers forced them to wear [alternative] black jerseys without numbers because their jerseys had the yaz, the Amazigh symbol, and the team’s name written in our alphabet. If they are able to intervene even in a children’s football championship, you can imagine the rest,” says Ben Khalifa.

Repression against his people in Algeria, he adds, has increased “exponentially” since 2019. Despite being weakened by illness, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika proposed himself for a fifth term at that time. The people reacted, and the Kabyles joined the crowd that peacefully took to the streets of the country’s main cities every Friday. In addition to demanding an end to military rule and corruption in Algeria, they also called for the modernisation of the country through democratic rule.

This did not happen. Amnesty International reports that at least 280 activists and human rights defenders remain in Algerian prisons after peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly. “The Algerian authorities crush all forms of dissent,” the NGO concludes. Similarly, a September 2023 Human Rights Watch report points to “increased repression” against opposition parties, civil society organisations, and media linked to the protest movement launched in February 2019.

Fathi Ben Khalifa goes further and claims that Algiers has taken advantage of three “screens” to hide the repression of its people from the rest of the world: the pandemic, the conflict with Morocco, and the war in Ukraine.

“The international community has simply forgotten to monitor respect for human rights in Algeria,” concludes the Libyan activist.

Identities

In terms of minority rights, Algeria has ratified the main international standards on paper: it voted in favour of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 and gave constitutional recognition to Amazigh as an official language in 2016. It is this patina of legitimacy that, a priori, makes it difficult to understand the levels of repression against a movement that has always pursued its objectives peacefully.

But let’s talk about one of the most sensitive issues in Algeria. The fact that even six well-known analysts contacted by this news site refused to answer questions for fear of reprisals (arrest for those living in Algeria and loss of visas for those living abroad) gives an idea of the depth of this identity fault line.

Silvia Quattrini, North Africa analyst at Minority Rights Group (an NGO working with more than 300 partners in 60 countries and in consultative status with the United Nations) traces the construction of Algeria’s national identity since independence in 1962 to a “purely Arab and Muslim” character, a factor that removes the Amazigh people from the equation.

“If we look back, we see that all the positive steps towards the recognition of this people have been made after moments of great tension and confrontation,” explains Quattrini. “In the mid-1990s, a year-long strike by students and teachers led to the creation of the High Commissariat of Amazighity; in 2001, we witnessed the Black Spring, those peaceful demonstrations in Kabylia that resulted in more than a hundred deaths and thousands of injured and arrests. Shortly afterwards, a constitutional amendment made Amazigh the second national language. However, in recent years, there has also been an upward trend in concessions, while attempts are being made to maintain total control while adopting restrictive measures against the Amazigh community itself,” she adds.

Quattrini recalls that during the 2019 anti-government protests alone, hundreds were arrested merely for carrying symbols such as the Amazigh flag. “In addition to being recurring victims of police violence and arbitrary arrests, activists of the MAK,” a movement calling for Kabylia's self-determination, “also suffer administrative discrimination or loss of employment. Some even have their passports seized by the Algerian Interior Ministry,” Quattrini stresses.

In October 2022, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention ruled that Algiers had not provided evidence that Kamira Nait Sid’s conduct was a threat to national security, nor was there any specific mention of any act of terrorism committed by her. Her detention, according to the report, is arbitrary and a result of her membership in the Amazigh community and her rights-oriented activities.

“Kamira is a woman who fights for democracy and human rights and is also a symbol of Kabylia. That is why she is under arrest.” This is the reading by Soraya Sough, the representative of the Movement for Self-Determination of Kabylia (MAK) for Southern Europe.

Based in Barcelona since 2009, Sough recalls that Nait Sid was one of the founders of the Black Spring Women’s Association. “She is a very brave woman who has broken many moulds. She has been able to incorporate modern tools into the historical struggle of Kabyle women. She has never been afraid, despite huge personal costs to herself. Kamira embodies the free Amazigh woman: that, in itself, is a challenge to the regime,” she adds.

In addition to Nait Sid’s case, the Amazigh representative points out that more than 500 MAK members are currently imprisoned in Algeria. Founded in 2003, the MAK has evolved from advocating for autonomy to demanding self-determination for Kabylia. It is also one of two organisations officially listed as “terrorist” in Algeria as of May 2021 (the other being the Islamist movement Rachad). However, repression in the country seems to leave no door unturned.

“Activists, human rights defenders, journalists, or even people not openly criticising the government... anyone can be arrested. Right after you raise your voice, you have to prepare yourself for immediate arrest, torture, or disappearance,” explains Sough. She states that the Algerian government “has unmasked itself.”.

Kabyle demonstrators in Algiers

Kabyle demonstrators in Algiers “It is now officially a military regime. There has never been a future for us in Algeria, even before independence,” laments this Amazigh woman who has not set foot in her homeland for six years. She knows that going back would land her in prison.

“Difficult times”

After visiting Algeria last September, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association, Clément Nyaletsossi Voule, recalled that Kamira Nait Sid had been the victim of arbitrary detention and called for her immediate release. Voule also denounced “the climate of fear generated to silence the demands of a large part of the population for constitutional reform and the establishment of the rule of law.”

Concerns over Nait Sid’s situation and the vulnerability of any dissident voice in Algeria are also made visible through NGOs, support platforms, or initiatives of political parties never including the largest ones. Catalan party Junts per Catalunya asked in the European Parliament in December 2021 whether the EU was monitoring Kamira Nait Sid’s criminal proceedings and whether any plans were in place to assist the prisoner with legal, medical, and psychological support.

In a February 2022 answer by Josep Borrell, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Vice-President of the European Commission, it was reaffirmed that attention is being paid to “human rights developments in Algeria, including in particular the situation of activists such as Ms Kamira Nait Sid.” However, it also recalled that “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms is enshrined in the Algerian Constitution” and called for “deepening an opening dialogue with Algeria, based on trust and constructive criticism.”

Eight months after that reply, in the face of the inaction of the high European authority, Borrell received another letter in which 13 MEPs from different left-wing parties accused him of “turning a blind eye to a regime that does not respect human rights” and called for a review of the agreements with Algeria.

Beyond the European Parliament, more and more voices warn of an attempt to buy silence with gas. Jesús A. Núñez, co-director of the Institute of Studies on Conflicts and Humanitarian Action (IECAH), says he fears that “the urgency of EU countries to eliminate their energy dependence on Russia will lead them to be even less interested in addressing the human rights violations that may be committed by alternative suppliers.”

Everything points in this direction, especially following Borrell’s statements after meeting President Abdelmadjid Tebboune in Algiers last March: “Europe receives 90% of Algerian gas exports. We know that we can count on Algeria, a reliable partner that has gone through difficult times.”