News

Sami languages revive in their diversity

The different Sami languages

Sami languages belong to the Finno-Ugric linguistic family, such as Finnish, Estonian, Livonian, or Hungarian. The diversity of Sami languages, each with a different number of speakers, makes it impossible to simplify them in a single linguistic situation. In the past, Sami was made up of a group of at least 14 languages; 9 are still spoken today. Some have gradually disappeared from the territories where they were spoken. That affects their protection, because linguistic domains are not aligned with nation-state borders, and each state's policy varies according to its democratic traditions.

Sami is a pluricentric language divided into two large blocks. The Western Sami languages are South Sami (500 speakers), Ume Sami (20 speakers), Pite Sami (20 speakers), Lule Sami (between 1,000 and 2,000 speakers), and Northern Sami (about 26,000 speakers). On the other hand, the Eastern Sami languages are Skolt Sami (320 speakers), Inari Sami (300 speakers), Kildin Sami (600 speakers), and Ter Sami (2 speakers). Unfortunately, these are approximate figures, as it is difficult to quantify the exact number of speakers.

There is some geographical continuity between the Sami languages. This is to say that speakers of neighbouring languages can get along with the speakers of nearby villages since each of these languages also has different dialectal variations. However, the Sami languages are assumed to exist together, with equal rights. No Sami language is above another, regardless of the number of speakers. In Sápmi, whether they are Sami speakers or assimilated by the other hegemonic languages, there is a maximum of 100,000 Sami distributed between the four countries: 40,000 to 60,000 in Norway, 15,000 to 20,000 in Sweden, 10,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia..

A sign in three of Norway's Sami languages. / Photo: David Córdoba Bou

A sign in three of Norway's Sami languages. / Photo: David Córdoba BouNorthern Sami, Lule Sami, Southern Sami, Inari Sami, and Skolt are the five languages allowed for use in public services and taught in schools in the three Nordic countries. Languages with only a couple of dozen speakers, known as moribund languages, also have revitalization processes but are focused more on documentation and the creation of materials.

The four states that divide Sápmi

In the middle of the 19th century, processes of nation-state building made the Sami suffer from all sides. They were mistreated and considered uncivilized people. They separated the youths from their families and interned them far away intending to assimilate them culturally and linguistically. The violence of forsvenskning (Swedification), Norwegianization, etc., prohibited the study of Sami and broke any contact with native culture. This changed during the 1960s in Sweden and Norway, and a decade later in Finland. Sami languages left behind a century of assimilationist policies by entering school. Slowly things changed. They began to establish institutions and rebuild everything that had been neglected. At present, the Sami have parliaments in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, responsible for advising on the creation of cultural policies, although it is the state chambers that legislate. In Russia, the Kola Sami assembly is not recognized by the Kremlin and has been inactive for years. However, its members are also part of the Sami Parliamentary Council, where representatives from the four countries meet..

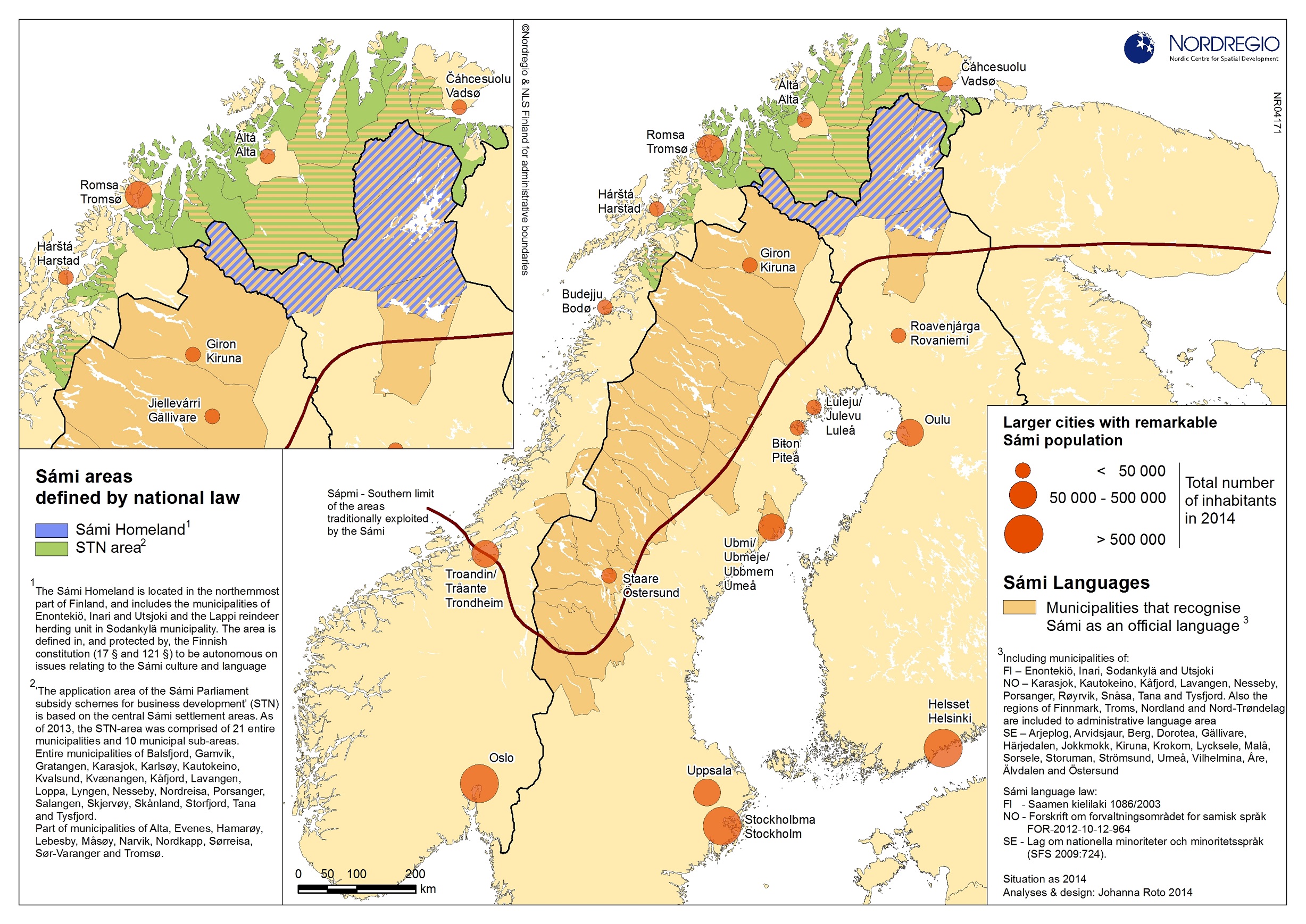

The Sami areas, as defined by state laws. / Map: Johanna Roto/Nordregio. A better resolution version of the map can be found following this link.

The Sami areas, as defined by state laws. / Map: Johanna Roto/Nordregio. A better resolution version of the map can be found following this link.There are five official minority languages in Sweden, including North Sami, South Sami, and Lule Sami. In Finland, in the north of the region still known as Lapland, Inari, Skolt, and Northern Sami have official status. Meanwhile, in Russia, the situation is much more complicated. Languages are written in the Cyrillic alphabet. A few decades ago, the Akkala Sami language went extinct. Ter Sami is dying out. Kildin Sami is currently a critically endangered language. Without an educational model, without generational transmission, and with a very dispersed community, the language faces a deadly future. Norway, where the Sami community is more numerous, is where they have obtained more rights. This can be seen in the Norwegian Constitution, which grants equal status to the Sami and Norwegian languages. It is also the only Scandinavian country, so far, that has signed and ratified ILO Convention 169 on indigenous and tribal peoples.

The Norwegian paradigm

Before the establishment of national borders, the Sami were semi-nomadic. Reindeer herding and fishing are still the main ways of life. The current territorial organization draws from an ancestral institution; the reindeer grazing districts (Siida). Sápmi is a very extensive and heterogeneous territory. There are no autonomous regions in the vast Norwegian area. Thirteen are the areas where Sami has the same linguistic rights as Norwegian (Samisk språkforvaltningsområde). Four municipalities for Southern Sami, one for Lule Sami, and the rest for Northern Sami.

Northern Sami is the language with the most visibility. This is because it is by far the most widely spoken and the only Sami language that is officially recognised in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. It was also the first language to be taught. Since the 1990s, Giellaealáskahttin, the Northern Sami word for language revitalization, has been one of the foundations of the work of the three Sami parliaments. The municipalities of the Samisk språkforvaltningsområde have three Sami school models according to capabilities and needs. The first one involves Sami immersion. Teachers and students speak fluently, and they live in Sami-speaking communities. The second option is a bilingual model. The third one is dominated by Norwegian, because it is the language of the local community, and the students’ knowledge of Sami is limited.

While Northern Sami has strengthened, others such as Southern Sami, with very few speakers and a large geographical area to cover, continue to struggle. One of the results of Norwegianization was the breaking of oral transmission from parents to children in places such as Romsa (Tromsø) and the entire coast of Finnmark, as well as in the areas of the south and Lule where it was historically spoken. Lásse-Ivvár Erke is a politician from the Norwegian Sami Association, a member of the Sami Parliament of Norway, and adviser to the president of that parliament, Elle-Rávnná Eli Silje Karine, the top Sami political authority. His ancestors were all Sami, but he learned the language at school because of Norwegianization. “Anywhere in Norway you can study the Sami variant you want, and you can do all the subjects if there are at least 10 people in the class.” The Sami centres are another option for learning any of the languages. “They are crucial. Despite this, more needs to be established. There are courses for adults, thematic courses in Sami.”

Northern Sami, a model of success

Kárášjohka is the Sami capital of Norway. All kinds of institutions are based here. Year after year, new ones continue to be established. The latest addition is Sámi Giellagáldu, an organization created in 2022 that decides issues related to any of the Sami languages: terminology, normalization, toponymy... “When a new word appears, the institution regulates languages, because otherwise, words become different adaptations from Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or Russian, and that destroys the language,” says Erke. A key feature of Sámi Giellagáldu is that it is coordinated among the three Nordic parliaments. But the most serious problem is the lack of teachers. “Since 2020 we have been working with an updated curriculum, although we have not yet finished adapting the one from 2010. Sami speakers can work in the public sector easily. That is why we need to create status”, that is, to increase the job's prestige, “to strengthen the teaching staff.”

Northern Sami has become a popular language. These are the words of Anni Østby, a representative of the Center Party and a high school Sami language teacher: "It is so popular that I teach distance learning to people from the south of Norway, who live there for work."Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino) and Kárášjohka (Karasjok) in Norway, and Ohcejohka (Utsjoki) in Finland, are the core of Northern Sami, the area where Sami speakers are the majority. It is common to find the inhabitants of these villages dressed in colorful gákti, the traditional Sami clothing that is also experiencing a comeback among younger people. “North Sami society revolves around reindeer. Those who have kept the reindeer have kept the language”. In Norway, the Norwegian language is studied in two standard models, which are presented as two languages; Bokmål and Nynorsk. “In Kárášjohka we removed Nynorsk to learn Sami. Although Sami is optional, in Kárášjohka it is learned by 80% of students. “I dare say Guovdageaidnu is 100 percent.” Despite its good reputation, the fight persists.

Čálliid Lágádus is one of the most prominent Sami publishers. Its founder Lemet-Jon Jovnna explains how the titles are originally published in Northern Sami, and then translated into Southern Sami and Lule Sami. “Books must have the same level as Norwegian. The three Sami languages must be equal. Southern Sami has a larger geographical area than Northern Sami, it is difficult to find common ground because each language has a different need,” Jovnna complains. Smaller languages, such as Southern Sami or Lule Sami, do not have competent teachers. “More school books are needed, more investment. Sami students compare themselves to the Norwegian system, which is parallel, and many end up buying books in Norwegian. All three languages have the same budget, 20 million Norwegian kroner (less than 2 million euros) per year, which must be shared between the three languages, but that is not enough.”.

Synnøve Solbakken-Härkönen, director of the Sami secondary school in Kárášjohka. / Photo: David Córdoba Bou

Synnøve Solbakken-Härkönen, director of the Sami secondary school in Kárášjohka. / Photo: David Córdoba BouGetting more funding is the job of parliament. The work of the Sami secondary school in Kárášjohka is decolonial. According to its director Synnøve Solbakken-Härkönen, “our mission is to try to decolonize the Norwegian system. Protect the land and our language, and teach values, indigenous philosophy, and traditions. We explain, from decoloniality, the daily impact of being divided into four states.”

The revitalization process of the Sami languages will surely be a process without a date limit. However, this Nordic model is for sure an example for other indigenous peoples and national minorities. They need to continue building it to survive because the threat is constant.