News

Kashmir’s year and half in the dark

Suspending the special status of Jammu and Kashmir was a Modi vow. In early August 2019, words became deeds

Suspending the special status that Jammu and Kashmir had hitherto enjoyed: that was one of the vows with which Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi secured his re-election to office. In early August 2019, words became deeds when Home Affairs Minister Amit Shah announced in Parliament the abolition of Article 370 of the Constitution, which had granted privileges to Jammu and Kashmir, such as the right to have its own constitution and flag. The territory became divided into two parts, both under the direct control of New Delhi. Seven million people were confined to their homes under a strict military curfew.A region forcibly disappeared

The removal of the region’s special status was followed by the abolition of another article, 35A, which prevented non-residents of Jammu and Kashmir from buying property and living there permanently. This was the first of several provisions with which the Modi government seeks to alter demographics —taking illegal Israeli settlements and the Chinese occupation of Tibet as references— and to replace Kashmir’s Muslim majority with a Hindu one, aligned with the notion of Hindutva —the agenda under which the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the party led by the prime minister, seeks to identify India on the basis of Hinduism as its majority faith.

Being an internationally disputed territory, the issuance of more than three million domicile certificates to non-Kashmiris contravenes international law, as population transfers are prohibited under Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and condemned by the UN Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. In 2019, Genocide Watch issued a genocide alert for Kashmir, as the group considered that the new housing policies endanger the indigenous, local population.

In addition to demographic assimilation, a strategy of economic expropriation of the region’s resources —with the granting of mining rights to Indian companies and the creation of land banks for investment— must be mentioned too.

Its autonomy lost, the Kashmir Valley has been under military and digital siege since August 2019. Within two weeks, nearly 4,000 people —including youths and two former Kashmiri chief ministers, Omar Abdullah and Mehboob Mufti— were arrested under the Public Safety Act (PSA) and sent to remand, where many remain today.

After Article 370 removal “terrorism in Kashmir will end,” argued Amit Shah, referring to armed groups receiving support from Pakistan. The government also argued that this would lay the foundations for economic prosperity and foreign investment in the territory. A year and a half later, Kashmir remains volatile and economically fragile —with the highest unemployment figures in 45 years—, a situation exacerbated by the six-month internet shutdown —estimated to have resulted in losses of $5.3 billion— and the subsequent pandemic lockdown. According to India’s Software Freedom Law Centre, the country is one of the world leaders in internet shutdowns, with 176 cases since they began monitoring the situation in 2012.

Its autonomy lost, the Kashmir Valley was put under military and digital siege. Within two weeks, nearly 4,000 people were sent to remand, where many remain today. This is compounded by the suppression of the right to assembly and freedom of expression

Between August 2019 and February 2021, the Kashmir Valley has undergone the largest internet blockade ever imposed by a democracy. Under the premise of “precautionary measures”, the government has imposed cuts in network access, a blockade of all digital communication channels, and restrictions on the movement of people. According to the organisation Access Now, several people have been harassed and/or arrested for using a virtual private network (VPN) to bypass the blackout. In January 2020, the Supreme Court of India compelled the government to follow a set of legal norms and constitutional standards when imposing the blockade. Two months later, authorities restored access to 2G, postpaid services, and websites available to the rest of the country, but not 4G access. However, according to an Access Now investigation, the government might be exchanging information with US software multinational Cisco Systems to build a firewall to prevent access to social networks.The climate of mass arrests and imprisonment, state surveillance, and conversion of hotels into detention centres is compounded by the suppression of the right to assembly and freedom of expression. Reports have emerged of people released from prison being forced to sign “pacts of silence.” To this must be added the dismantling of the economy, the education, and the local judicial system. Jammu and Kashmir bodies such as the Children’s Commission or the semi-autonomous Human Rights Commission have been abolished, and more than 600 habeas corpus petitions by people seeking missing relatives have been put on hold.

New Delhi’s attempt to reprogram the Kashmiri economy and society has given way to a new wave of repression, with weekly violent confrontations between Indian troops and a new generation of militants. Since 2020, Indian authorities have buried several Kashmiri rebels in secret, unmarked graves, denying the families’ right to hold funerals and increasing anti-Indian sentiment in the valley. According to the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), from 1 January to 30 June 2020, 229 killings were recorded during more than 100 military operations in the region. These included the extrajudicial killings of 32 civilians.

Furthermore, since the uprising against New Delhi’s control in the late 1980s, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) puts the number of missing people in Kashmir at between 8,000 and 10,000. What was initially a largely peaceful movement against India’s occupation turned into an armed revolt in 1989, following a series of broken political promises and persecution of dissenting voices.

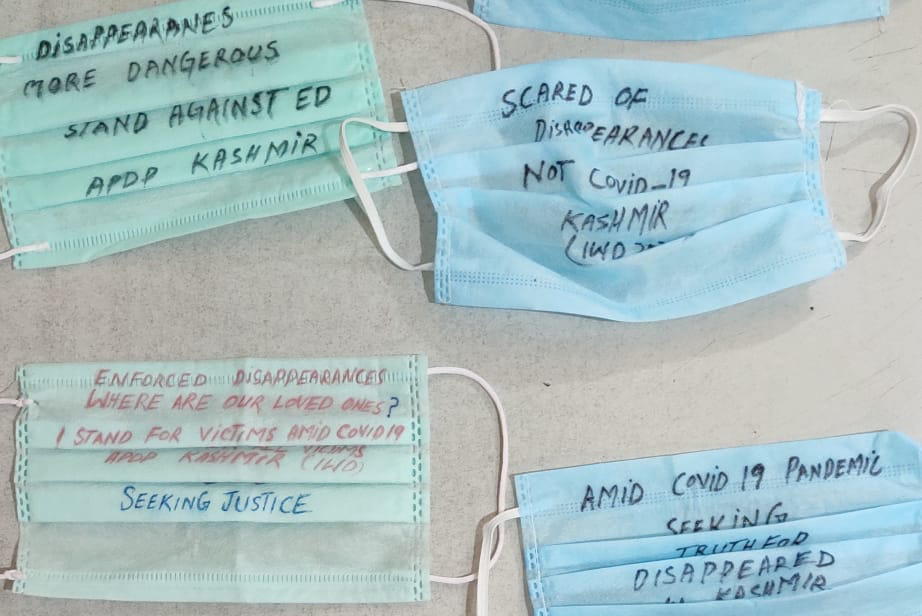

An APDP-organized protest during the pandemic uses masks to denounce forced disappearances in Kashmir. / Photo: JKCCS

An APDP-organized protest during the pandemic uses masks to denounce forced disappearances in Kashmir. / Photo: JKCCSThe “first case of mass blindness in history”

Aamir Ahmad’s life took a radical turn in 2017. A first-year Law student, he was attending a martyr’s funeral when three police vehicles fired into the crowd with air guns, which the government describes as “non-lethal” although between 2016 and October 2020 more than 10,500 people have gone partially or totally blind after being hit by a pellet, according to the Kashmir Media Service. Aamir was hit by one of them. After undergoing four surgeries in Srinagar and Amritsar, a city in neighbouring Punjab, he lost the sight in one eye. Three years later, in January 2020, he set up the Association of Pellet Survivors to share doubts and experiences about the financial, social, and psychological problems faced by more victims of police repression.

More than 10,500 people have gone partially or totally blind after being hit by a pellet shot by the police. “The government gives no social assistance to the victims, accusing us of being guerrillas,” Aamir says

“The government gives no social assistance to the victims, accusing us of being guerrillas,” says Aamir. Victims receive certificates with no more than 30% disability if they have been blinded in one eye, or 70% for the loss of sight in both eyes. According to a 2019 study, 85% of victims suffer from psychiatric problems such as trauma, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. This is aggravated by the fact that few receive treatment, due to taboos associated with psychiatry, a lack of financial resources, and severe depression.In 2017, Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s representative to the United Nations, condemned India’s use of air guns as the “first case of mass blindness in history.” According to the second report on human rights in Kashmir by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, between mid-2016 and the end of 2018 at least 1,253 people were totally or partially blinded by pellet shots. Official figures, Aamir argues, are but a small part of an incomplete picture where victims do not go to hospitals or prefer not to give their names for fear of reprisals.

Press freedom and freedom of expression under persecution

In October 2020, police raided the headquarters of the Kashmir Times in the Kashmir Valley capital Srinagar and shut them down, with all the equipment, computers, and printers inside. Due to a lack of revenue and financial stability, like many other regional and local media, the newspaper was renting part of a government building for its newsroom. The closure came without legal safeguards or previous notice. Anuradha Bhasin, editor of the Kashmir Times, describes it as an attempt to silence the paper’s voice. Bhasin had become one of the most critical voices against the abolition of Article 370 and the subsequent communications blockade, which she denounced to the Supreme Court. “The Indian government is completely intolerant of criticism, particularly if about Kashmir,” the journalist says.

“This is a climate of fear, in which local newspapers do not publish relevant stories, and journalism has become a state’s public relations department, despite this being one of the most turbulent periods in Kashmir’s history,” Anuradha Bhasin argues

“It has always been difficult to be a journalist in Kashmir, especially in the last 30 years,” says Bhasin, referring to a framework of actors —including the Indian state, the political establishment, and armed militants— who try to control the press. However, in the last year and a half, she believes journalism has found itself in an untenable situation of paralysis with the passing of new laws that allow the police and cyber-police to bring criminal charges against journalists who report human rights violations. “This is a climate of fear, in which local newspapers do not publish relevant stories, and journalism has become a state’s public relations department, despite this being one of the most turbulent periods in Kashmir’s history,” she concludes.Legislation with which the Modi government regulates journalistic activity includes the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), an anti-terrorism law under which photojournalist Masri Zahra was arrested in April 2020 on charges of posting “anti-national” content on social media. It can also be mentioned the newly revised Media Policy, which allows government officers to scrutinise media content and decide which news is “false,” “unethical,” and/or “anti-nationalist,” in addition to sharing information with state security agencies and taking legal action against journalists and organisations. The Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) denounces how these tactics infringe on the rights to freedom of press and expression and “signal a forewarning for media personnel to adhere to the state narrative.”

“Looking at the current situation of censorship, it seems that critical voices will find it increasingly difficult to survive,” Qazi Zaid fears

“Much of the media is muzzled, and this situation makes us question the indirect censorship we have been plunged into due to the lack of advertising revenue and the lack of a functioning market economy as it should,” agrees Qazi Zaid, editor-in-chief of the Free Press Kashmir weekly. Many media outlets are dependent on the government for funding and advertising, which results in yet another content regulation. “Looking at the current situation of censorship, it seems that critical voices will find it increasingly difficult to survive,” Zaid says.A valley between three nuclear powers

On 17 June 2020, a confrontation between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley —along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) of the Kashmiri border— resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers including a colonel, the highest number of casualties in a clash with China since 1967. A few days earlier, Modi had addressed the Indian people and denied that Chinese troops had stormed into Kashmiri territory, although events in Galwan suggest otherwise.

The Galwan confrontation marked a shift in Narendra Modi’s military policy after he had come to power, promising to abandon India’s stance of military containment vis-à-vis neighbouring Pakistan and, to a lesser extent, Chinese expansionism. The clash also hindered India’s accession into the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trade agreement between 15 Asian countries that New Delhi also refused to sign over fears of Chinese imports.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo: Kremlin.ru

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo: Kremlin.ruMoreover, fires with Islamabad were stoked by statements such as those of Amit Shah, who claimed in Parliament that he was ready to “lay” his “life for Kashmir” and for recovering the territories of what the Indian government calls “Pakistan Occupied Kashmir,” or “POK”, as well as the Chinese border areas of Aksai Chin. The Indian meteorological department went further by including Gilgit-Baltistan —a Pakistan-controlled territory of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir— on its maps. However, after months of tensions and fire exchange on the border, the two powers signed a ceasefire at the end of February 2021.

Joe Biden’s arrival to the White House hints at possible changes in the US stance on India and Kashmir. In September 2019, during the campaign for the Democratic nomination, current Vice President Kamala Harris stated “we are all watching [Kashmir]” and implicitly attacked the Modi government for human rights violations in the territory. Likewise, in his Agenda for Muslim-American Communities, Biden noted that “the Indian government should take all necessary steps to restore rights for all the people of Kashmir,” being much more critical of New Delhi than his two predecessors: Trump’s affinity and sympathy to Modi before thousands of Indo-Americans in Houston (Texas), and Obama’s support for the BJP leader’s first term in office, a time when the Indian government’s priority was to grow foreign investment and Obama lifted the visa restrictions on Modi that George W. Bush had placed on him in response to the 2002 Gujarat riots.

Lastly, another power is gaining weight in the region: Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey, Pakistan’s historic ally. In a message for the 75th anniversary of the United Nations, Erdogan warned that the Kashmir conflict “is key to the stability and peace of South Asia” and declared himself “in favour of dialogue,” a message that was read as a foreign interference by New Delhi, but welcomed by Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan.