News

Mongolian government seeks to spread official use of traditional alphabet by 2025

Mongolian script to coexist with Cyrillic in Asian country · We explain other cases of alphabets closely linked to minoritised languages

The Mongolian Parliament approved in 2015 that the authorities of the Asian country would introduce the use of the traditional alphabet, or bichig, within 10 years, alongside Cyrillic —which remains the dominant form of writing. In the last phase, starting in 2025, this is planned to include official communications, identity cards, and the public display of the alphabet.

The government has now announced that it is entering the third phase of the implementation of the plan. One of its main axes will be the setting of digital tools for the use of bichig. It is a considerable challenge given the fact that, until now, the introduction of the Mongolian alphabet into information technology standard Unicode has been problematic. Authorities now say they want to solve it.

In China’s Southern —or Inner— Mongolia region, bichig has been in continued use, authorities there keeping some websites and public signs in it. In Mongolia proper, some websites —such as the president’s— also include a version in the Mongolian alphabet.

The Mongolian government aims at bichig being used in e-mail writing, as well as in on line media, alongside Cyrillic.

The Mongolian alphabet is derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet, and is written vertically. It was introduced by Tata-tonga in the early 13th century.

The Mongolian government officially introduced the use of the Latin alphabet in 1930, which was replaced in 1941 by Cyrillic, under the influence of the Soviet Union.

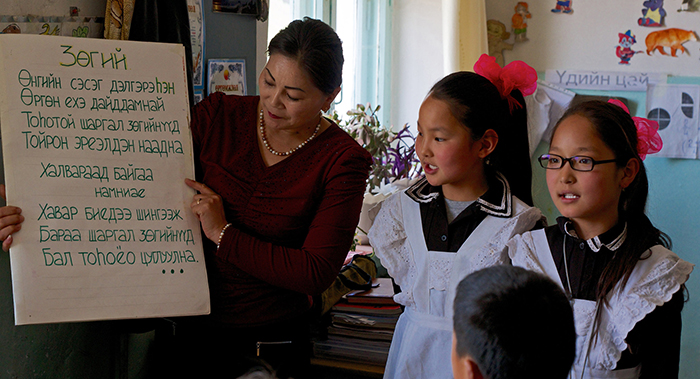

A school in Mongolia. The Cyrillic alphabet has been used since 1941 to write Mongolian. / Photo: World Bank Photo Collection.

A school in Mongolia. The Cyrillic alphabet has been used since 1941 to write Mongolian. / Photo: World Bank Photo Collection.Other languages that used to be written in Cyrillic have abandoned it since the fall of the USSR. Azerbaijan introduced the use of the Latin alphabet for Azeri in 1991, while Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan took the same decision for Uzbek and Turkmen in 1992 and 1993 respectively. In 2018, Kazakhstan announced that Kazakh would abandon Cyrillic for Latin by 2025.

In 1989, already before the end of the USSR, Moldova had applied the same transition to the Romanian language. Transnistria, however, continued to write Romanian in Cyrillic, which had in fact been the alphabet in which the language had been written in Romania itself until the 19th century.

Alphabets as an feature of language identity

It is no secret that having a different alphabet is a fundamental feature of identity for many languages. Well-known cases among state languages include Greek, Georgian, Armenian, Amharic, Chinese, Korean, or Japanese —which combines its own set of characters with others taken from Chinese.

Others are more unknown, particularly those used by some minoritised languages. To write Amazigh, for instance, the Tifinagh alphabet is used in Morocco, Libya and in some countries of the diaspora, such as Catalonia. The version of the Tifinagh alphabet currently in use is a modern adaptation of a 3,000-year-old writing system, kept alive by the Tuareg. The letter ⵣ, corresponding to the English “z”, has become the symbol of the Amazigh people, and is found on their flag.

Tifinagh is one among dozens of alphabets under threat, according to the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets, a project by an NGO from Vermont (USA) that seeks to support the preservation of those writing systems.

Within the United States themselves, one very peculiar writing system is Cherokee. It is a syllabary —characters represent whole syllables instead of individual sounds— devised in 1821 by Cherokee polymath Sequoyah. Some of its characters are similar or identical to those in the Latin alphabet, but are pronounced differently. Thus, “K” reads “tso”, and “W”, “la”.

This is an animated video in Cherokee, with English subtitles, that tells the history of the syllabary, from Sequoyah’s time to present-day smartphones:

The African continent too developed several writing systems during the 19th and 20th centuries. The Vai syllabary, created in the 1830s to write the Vai language of Liberia, is one of the most successful ones. Its father, Mɔmɔlu Duwalu Bukɛlɛ, is believed to have devised it together with five assistants after having had a dream revelation. Since then, this writing system has been closely linked to the identity of the Vai language, as it is one of the few in the region not to use either the Latin or Arabic alphabets.

Geographically close to it, the N’Ko alphabet was created in 1949 in Guinea by Solomana Kanté, who aimed at helping to decolonize West Africa’s Mande languages. Kanté thought that, by providing them with their own writing, their dignity and identity was being claimed in the face of European domination.

Alphabets for minoritised languages are still being produced in the 21st century. This is the case for Wancho, a writing system created from 2001 to 2012 by local teacher Banwang Losu for the language of the same name. Losu is confident that his contribution will help preserve Wancho, spoken by some 60,000 people in India’s Arunachal Pradesh. The Asian country has the largest concentration of endangered writing systems in the world.

In other cases, such as Tifinagh seen above, the history of the alphabet goes back centuries or millennia. This is the case for the Tibetan script —essential to the identity of this nation and with origins in the 7th century AD or even earlier— or the Syriac alphabet, which was born by 200 BC and has been used throughout history to write no less than 10 different languages, in some cases closely linked to different branches of Christianity:

The alphabet, however, is now also a distinctive symbol of present-day Assyrian languages, which are struggling to survive in the Middle East. Their use in schools in Syria and Iraq and on official signs —for example, in Rojava— is helping to make the existence of the Assyrian people and their culture more visible.