News

Bougainville heads for self-determination vote, but independence might take long time —if it comes at all

In non-binding referendum, Papua New Guinea could block secession even in the case of a strong “yes” majority · Lengthy negotiations expected after the vote · Post-conflict peace has largely held, management of post-referendum period deemed crucial

Some 206,000 people, 18 or older, are eligible to vote in the referendum. This includes both Bougainvilleans and non-Bougainvilleans having lived in Bougainville for at least the past six months before the referendum enrolment process and being PNG citizens. It is estimated that Bougainvilleans outnumber non-Bougainvilleans. As for Bougainvilleans living outside the autonomous region, they must have links to a Bougainville clan by birth or adoption, by either parents or by marriage, in order to be allowed to vote.

The governments of PNG and Bougainville agreed to establish an independent agency, the Bougainville Referendum Commission (BRC), to conduct the referendum. It is chaired by former Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern.

The vote will span from 23 November to 7 December in polling stations across the islands and abroad, both in PNG and other countries where Bougainvilleans reside. BRG sources say the full two weeks are needed, as long as the vote will be “a large and complex operation spanning remote atolls and highlands of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, as well as all 21 PNG provinces, four additional work sites and four overseas locations. We experience frequent power outs, many locations do not have phone reception and transport and logistics are a challenge for any electoral process.”

The result could be announced by mid-December.

Many axes —including domestic politics, the consequences of conflict, the role of civil society, geopolitics, and economy— intersect in the referendum. To have a closer look into them, Nationalia has spoken to for experts involved in the referendum or its analysis: constitutional lawyer Anthony Regan, local consultant and Bougainville women’s leader Barbara Tanne, Chief Referendum Officer Mauricio Claudio, and senior lecturer in security studies Anna Powles.

Why has a referendum on independence been called?

The holding of a referendum was agreed by the PNG government and Bougainvillean representatives as a part of the Bougainville Peace Agreement (BPA), which was signed in August 2001 to put an end to a 1988-1998 conflict that saw the Papuan army fighting a local rebel group, the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA). The conflict turned more complex as years went by and intra-island infighting raged, claiming 10,000 to 15,000 lives. Protests over the economic, social and environmental effects of the exploitation of the Panguna copper mine, in the centre of Bougainville, led to the violent conflict, which also sat on grievances by Bougainvilleans against foreign domination —of European colonists in the first place and then of the PNG government— and a sense of a distinct identity that can be traced back to the 1950s and 1960s.

As per the BPA, Bougainville gained semi-autonomous status within PNG in 2005. The deal also foresaw that a referendum on Bougainville’s independence from PNG had to be organised within 10 to 15 years after the establishment of the Autonomous Bougainville Government (ABG), that is between 2015 and 2020.

So Bougainville already has its own government?

Yes. The ABG was inaugurated in 2005. It has a cabinet, Parliament, police and Constitution of its own. It enjoys a higher level of self-government than ordinary provinces of Papua New Guinea, but it is not yet exercising all the powers that the peace agreement grants to it.

Out of the PNG’s total population of 8 million, just a few less than 300,000 live in the autonomous region, the vast majority of them in the two main islands —Bougainville and Buka, where the interim capital is located. A few thousands live in scattered atolls. They speak some 20 different languages, with Tok Pisin and English used as linguae francae.

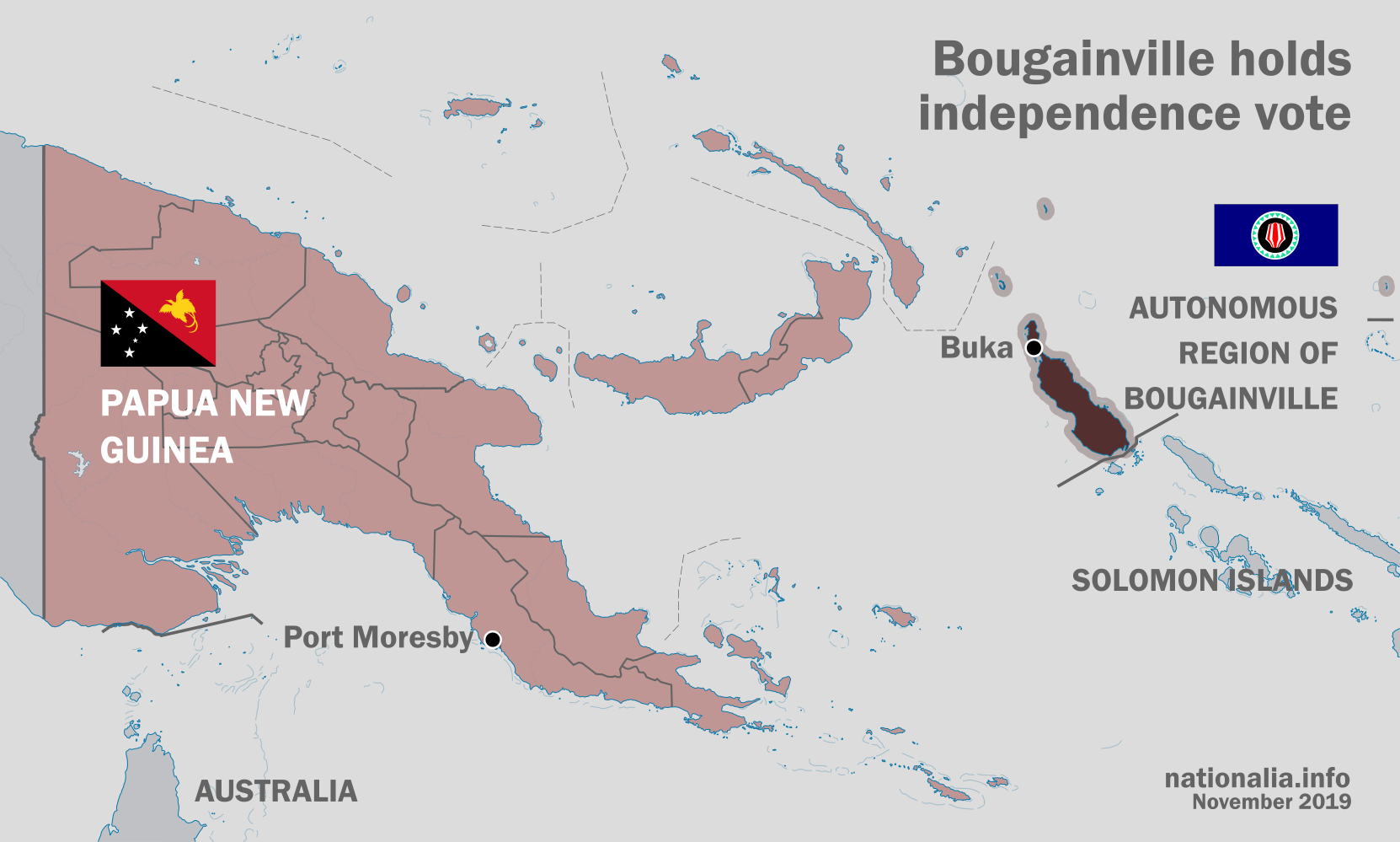

Bougainville is the easternmost insular region of Papua New Guinea. It is located some 900 kilometres from mainland PNG, and much closer to the Solomon Islands, with which it shares geographic, historical and cultural affinities.

Bougainville is the easternmost insular region of Papua New Guinea. It is located some 900 kilometres from mainland PNG, and much closer to the Solomon Islands, with which it shares geographic, historical and cultural affinities.What are the options to be chosen in the referendum?

Voters will be faced with two options on the ballots —either full independence or greater autonomy within PNG.

What the second option means is not as clear as the first one. Only in late October have the PNG and Bougainville governments issued a description of what both options mean, in which greater autonomy is described as a “negotiated political settlement that provides for a form of autonomy with greater powers than those currently available under constitutional arrangements.” Such powers could include “additional taxation and other revenue-raising powers,” among other areas.

“The Bougainville Referendum Commission recognises the importance of an informed vote for the result to be seen as credible to all parties concerned,” Mauricio Claudio tells Nationalia. “The Chair of the Commission had written earlier to the two governments for more detailed information on the two options.” The description issued “will greatly support the large amount of voter awareness already being provided to voters by the two governments during numerous joint government roadshows, and the BRC itself is providing information in multiple formats including face to face, materials, video and also its own roadshows. We believe it will be an informed vote.”

Why an option for statu quo is not being included?

“There is considerable dissatisfaction with the current autonomy arrangements, so that offering the status quo as the alternative to independence was always not going to be an option with a realistic chance of acceptance,” Australian National University’s Anthony Regan, one of the leading experts on Bougainville, tells Nationalia.

Earlier this year, Bougainville President John Momis told the PNG Parliament that the failure by the PNG government to pay but a fraction of a post-conflict restoration and development grant has “contributed to a growing sense of frustration amongst Bougainvilleans with the autonomy arrangements.”

So independence is on track to win the vote?

Most analysts think so.

“It is not 100 per cent certain that there will be a strong majority in favour of independence —there has been no form of opinion polling undertaken— but that is the most likely outcome,” Regan says.

According to a Lowy Institute estimation, it “appears a majority of Bougainvilleans —perhaps three-quarters or more— will opt to vote for independence.”

“I agree that Bougainville is likely to overwhelmingly vote for independence,” says Massey University’s Anna Powles, who specialises in geopolitics and security in the Pacific Islands region. “There has been a recent upsurge in voter registration, which often is an indication that voters are registering to ensure that the vote result is a ‘yes’ vote for independence.”

Is Bougainville thus likely to become the world’s newest independent state?

That is not so clear —the referendum result is not binding.

The peace agreement states that the “outcome of the referendum will be subject to ratification (final decision making authority) of the National Parliament,” that is, the Parliament of Papua New Guinea is ultimately vested with the power to make a final decision.

Both the PNG and Bougainville governments are insisting that a post-referendum bi-lateral negotiation will be needed. But it is far from clear that the PNG government will grant independence to Bougainville, even if the referendum result is clearly in favour of secession.

“It is quite likely that PNG will oppose independence,” Regan says.

Some media outlets have been hinting that the new PNG government under James Marape could be more open to negotiate a settlement that respects the spirit of the BPA than the previous cabinet of Peter O’Neill was.

But this remains to be seen. Marape, “during his election campaign, campaigned on a nationalist platform,” and “has strongly indicated his preference that Bougainville remain with PNG”, Powles recalls. “How others in Waigani feel is unclear.”

To this, PNG government’s fears of balkanisation must be added. “Various prime ministers during the 1980s and 1990s voiced those concerns,” Powles says. PNG is a very diverse country, with autonomist tensions in Enga or New Ireland. “How realistic those concerns are is less clear. Waigani to its credit has heeded a number of the lessons from the Bougainville conflict and applied them in those areas where there was dissatisfaction towards the central government over resource and extractive issues, for instance.”

Does economy play any role in this?

Certainly it does.

On the one hand, Bougainville is rich with mineral resources —especially copper and gold—, but their extraction has been at the roots of past conflicts. In the past, the PNG government made handsome profits from mining there. But the main mine, Panguna, is closed. It is uncertain whether it will be reopened, and who could make a profit from that.

On the other, the budget of the Bougainville Autonomous Government is a lot dependent on PNG government grants —which amount to more than 80% of it every year. Even if all tax collection were transferred to the Bougainville authorities, doubts remain on the sustainability of an independent republic in the short term, current data show.

“It is clear that Bougainville is a long way from achieving fiscal self-reliance,” Regan says. “That alone makes it certain that there would be a long delay before independence can be achieved, even if PNG were to agree to Bougainville becoming independent.”

The PNG government announced in September 2019 a 1 billion kina (260 million euro) plan to foster Bougainville’s economic independence.

Asked on how many years can be realistically expected that the transition to independence could last, Regan says “it might take ten or more years.” There is not specific transition period set in the peace agreement.

What if other countries tried to fund Bougainville independence?

It is, indeed, a possibility.

Some countries could have an interest to set foot on Bougainville, China likely to be one of them. “There are valid concerns that China could potentially step into the vacuum and provide support to an independent Bougainville,” Powles says. But the expert believes this could be “in exchange, most importantly, for diplomatic recognition of China over Taiwan. However, China also has significant interest in Papua New Guinea itself which is a much larger player in the extractive sector —both land based and marine. How China will seek to balance these potentially competing relationships will be very interesting.”

Other countries could be interested in the contrary. Indonesia is likely to be reluctant to Bougainville independence as it might set yet another precedent for the self-determination struggle in West Papua. Neighbouring Solomon Islands, even if they provided support to Bougainville refugees during the conflict and some of their top politicians expressed sympathy for the cause of independence, might also be concerned, because of their own past secessionist tensions in its western islands.

As regards PNG’s powerful neighbour Australia, Powles expects it to “recognise and respect the outcome of the Waigani decision,” following its current “careful” approach to the issue “given its considerable legacy issues (the infamous use of Australian military helicopters modified as attack helicopters in Bougainville by the PNGDF, is one example).”

Is a return to violence likely?

Together with the establishment of the autonomous government in 2005 and the holding of the referendum now, weapons disposal has been one of the so-called “three pillars” of the peace agreement. About 2,000 weapons were disposed and destroyed under the peace agreement plan, but an unknown number —at least hundreds of them— are still around. In summer, rebel Me’ekamui group was still surrendering guns.

“It’s vital for the credibility of the vote, for this process to be worthwhile, that those rightfully enrolled, no matter whether they are living in Bougainville or in PNG, can vote without fear and without intimidation,” Claudio says. “We strongly believe this will be the case. We strongly believe that everyone recognizes the importance, and the right, for the people of Bougainville to finally have their say.”

Experts asked by Nationalia are relatively optimistic. “A return to violence remains a possibility, but not a strong one,” says Regan. “There has been a fairly effective weapons disposal for the various militias in Bougainville.”

“New Zealand is leading a small regional mission comprising of police who are due to depart Bougainville shortly after the vote,” Powles recalls. “If instability emerged and the local Bougainvillean police were unable to quell the violence, it is likely that there would be some form of external assistance if PNG and the ABG invited it. Where that assistance would come from is less clear but most likely New Zealand and Australia.”

“We do have question of what reactions that may arise after the outcome of the referendum but we are positive and believe that the result be respected and accepted by everyone,” local consultant with Conciliation Resources, woman leader and a peace mediator Barbara Tanne tells Nationalia. “In doing so, there are peace building programs, peace dialogues and reconciliations from individuals, veterans, churches, women and youths including the ABG and national government,” Tanne adds.

How has civil society been involved in the peace process?

The 1988-1998 conflict left deep wounds in the Bougainvillean society, as killings and other gross violations of human rights took place, which for many years did not receive enough attention. “There is an unspoken presence of pain and grievance in many homes and villages associated with atrocities committed during the civil conflict,” writes journalist and Lowy Institute contributor Catherine Wilson. “Bringing justice to victims is an immense challenge given that there has been no investigation into the scale and details of atrocities,” the journalist goes on, and she warns that “there is some disquiet among many for how post-conflict Bougainville society will evolve over the next generation if impunity reigns for the wartime horrors which still plague people’s memories.”

Even though, Barbara Tanne highlights the other side of the coin, as for the last years, “a lot has happened”, such as “peace dialogues, mediation and reconciliations,” which “have already been done through the churches’ spiritual programs and traditionally.” According to her, this shows how “the civil society of Bougainville, in partnership with the ABG Department of Bougainville Peace Agreement, played a major role together in the peace process.”

“Our veterans, political leaders, women, churches... all played an important role,” Tanne goes on. “Remains of missing persons have been handed back to families. Weapons disposals and containment is also some a positive change or indication that gave confidence and assurance to our people, particularly the victims of the conflict. Peace and reconciliation programs will be ongoing programs for Bougainville.”

What about women?

Women rights groups have been active in mobilising to put an end to violence, in rebuilding society and upholding reconciliation efforts, while seizing opportunities to demand an amelioration of life conditions for women in Bougainville.

According to Tanne, “women built bridges between their own families, clans and displaced fellow Bougainvilleans when they realised that violations of human rights were increasing every day” during the conflict. “Without remuneration they have laboured to create basic services using whatever talent or means they had at hand. They demanded peace during negotiation meetings with their men folks” and “addressed issues to end the conflict, employing strategies such as silent marches, sit-in protests and peace marches —it is our Melanesian culture that women are peace makers, be it in families, clans and communities.”

Despite this role, women continue to be largely excluded from senior positions in the upper levels of governance. As an example, out of 41 members of the Bougainville Parliament, a mere 4 are women —3 are holding seats reserved for them.

Challenges go much further than that. Gender based violence is one of the more pressing, according to organisations and social leaders. “Violence against women and girls continues to show a negative impact, be it in public health, education and economic development,” Tanne points out. High rates of violence against women are prevalent throughout Bougainville, a 2019 IFES report reads, and “the culture of violence that emerged over the decade long civil war is linked with the escalation in violence against women and cases of domestic violence.”

Solving things the Melanesian way?

A concept, “the Melanesian way,” has been gaining circulation in the region, as a way to understand how the whole issue linked to the referendum and beyond can and will be solved. A mix of “consultation, conversation and consensus,” the concept has been recently mentioned by former independence fighters Dennis Kuiai and James Tanis —who is also a former president of the Autonomous Region—as a key basis on how both governments should deal with the post-referendum period.

Anna Powles elaborates on this: “If independence is not granted, there will be a very Melanesian approach to negotiating a political outcome through consensus —this could take years. My concerns lie in how expectations will be managed especially amongst the younger generation (particularly the male youth demographic) who were unable to prove themselves on the battlefield, so to speak, and will be wanting to prove themselves at the ballot box. How will their expectations be managed? The post referendum transition period is going to be absolutely critical for security and stability on Bougainville.”