News

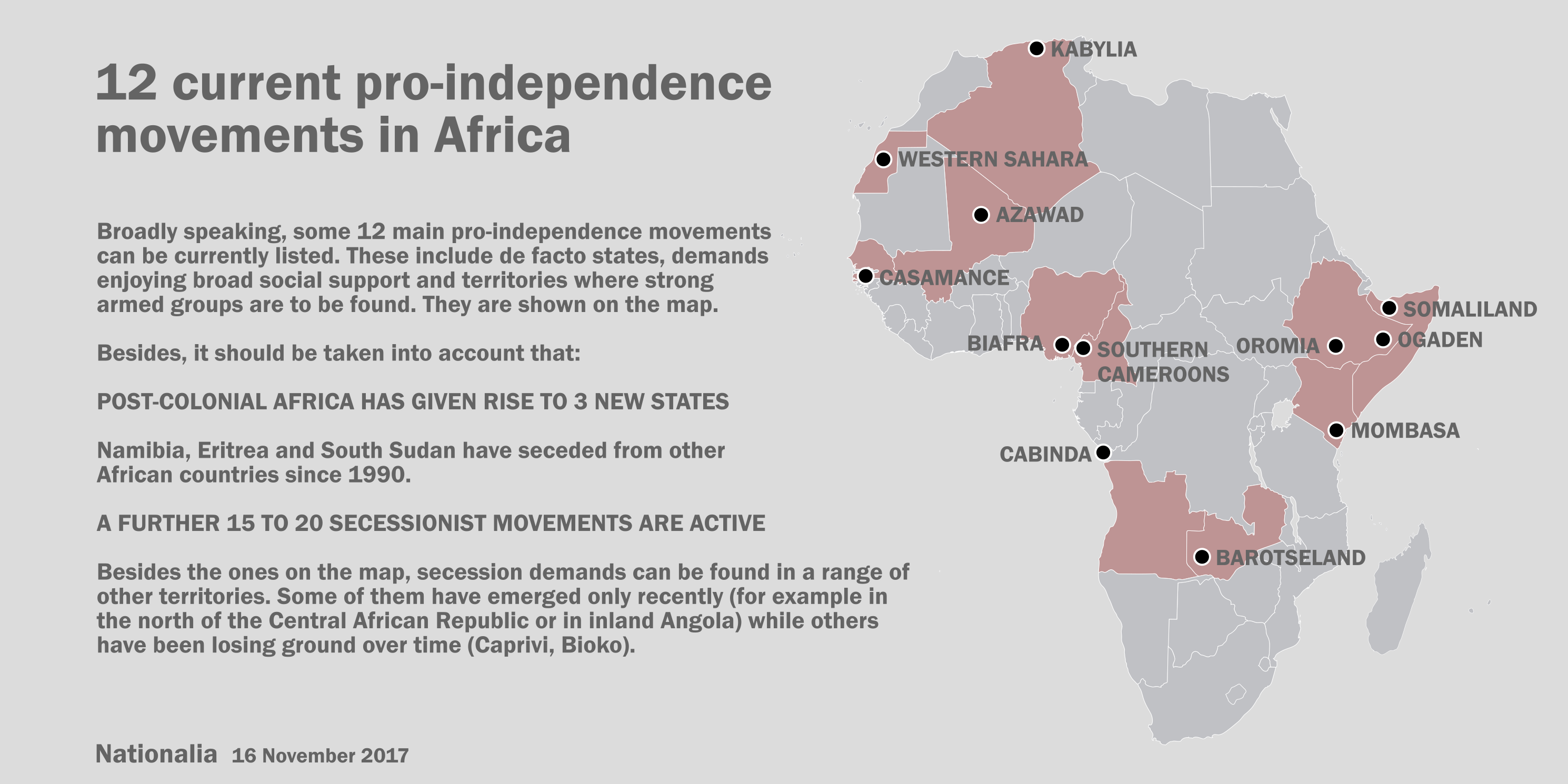

Post-colonial independence movements: a difficult task to become a sovereign country in today’s Africa

Somaliland

A country lying in the northwest of Somalia’s internationally recognized borders, Somaliland was colonized by the British while the rest of Somalia was dominated by Italy. In 1960 Somaliland was independent for five days, before joining the former Italian colony to make the new independent state of Somalia. In 1990, however, Somalilanders re-established their independence amid the chaos of the Somali civil war. Since then, Somaliland has held three presidential and two parliamentary elections. No other state has recognized its independence, even if it maintains diplomatic relations with neighbouring states such as Ethiopia —which holds a consulate in Somaliland capital Hargeisa— and Djibouti, as well as with several European countries. The United Arab Emirates and Somaliland signed an important diplomatic and military agreement in 2017.

Southern Cameroons

Unlike the rest of Cameroon —which was subject to French rule during colonial time—, Southern Cameroons was a British mandate territory before decolonization. A pro-independence movement has been active in Southern Cameroons since the 1970s. Common perception there is that the Cameroonian government has politically and economically marginalized Southern Cameroonians. After years of relative calm, tension is again on the rise since the end of 2016, when protests flared in Southern Cameroons asking the central government to facilitate the use of common law and to restore a pre-1972 system by which Cameroon was a two-state federation made up of Southern Cameroons and the formerly French part of the country. A group of Southern Cameroonians declaredsymbolic independence 1 October. Subsequent crackdown by the Cameroonian armed forces left dozens killed.

Western Sahara

Pro-independence, anti-colonial Polisario Front proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in 1976, after Spain —the colonizing power— illegally transferred the territory to Morocco and Mauritania. Morocco is currently occupying 80% of Western Sahara, where Moroccan settlers are altering the territory’s previous demographic makeup. The remaining 20% —mostly desert in the interior parts— is controlled by the Sahrawi Republic. The Polisario continues to demand, as agreed with Morocco in 1988, the holding of a referendum on self-determination. The Alawite kingdom, however, has withdrawn from its previous commitment, and now merely offers Sahrawis an autonomy plan. The Sahrawi population has repeatedly revolted against Moroccan occupation, most recently during the 2010-2011 Gdeim Izik protests.

Barotseland

Western Zambia’s Barotseland had been given a measure of recognition by the British during colonial rule, following the existence there of an indigenous traditional kingdom dating back to the 19th century. At the time of independence (1964), the Barotse king and the new Zambian government signed an agreement, by which Barotseland would retain a degree of autonomy. But the current Barotse pro-sovereignty movement complains that the Zambian government has not fulfilled its commitments, turning Barotseland into a non self-governing province and economically marginalizing it. Since 2010, several pro-independence protests have taken place to demand restoration of Barotse sovereignty.

Biafra

The independence of Nigeria (1960) was followed by various political, regional and ethnic tensions that reached their climax in 1966, when tens of thousands of Igbos were murdered in the north of the country in a mass pogrom. The following year, the Igbo movement proclaimed the independence of the state of Biafra, which included all of oil-rich southeast Nigeria, the homeland of the Igbo as well as that of other peoples. After a terrible war of independence against Nigeria (1967-1970) that killed between 500,000 and 2 million, Biafra was defeated. For decades, independence dreams had seemed gone. However, in the 1990s the secession movement began to reorganize itself and, since 2015, it has been carrying out mass mobilizations, always with the Igbo people as a support base.

Cabinda

Since the 1960s, several armed movements have sought to achieve Cabinda independence by military means. Cabinda is an oil-rich coastal exclave (that is, a territory without physical connection with the rest of the country) of Angola bearing certain pre-colonial and colonial features differentiated from the rest of the country. This fact is argued by pro-independence proponents as a proof that Cabinda never belonged to Angola. FLEC is the most important among secessionist political-military groups, but is at the moment internally divided. FLEC maintains an armed struggle against the Angolan army; in 2016 and 2017, clashes have left several people dead. The Angolan government not only chases FLEC members but also attacks the freedom of expression and association of non-secessionist Cabindan grassroots right groups. The most well-known case abroad is that of Mpalabanda rights group, which was banned by an Angolan court in 2006.

Kabylia

Unlike many other African independence movements, Kabylia is not based on a pre-existing colonial entity, but rather on the right to self-determination of a people defined in linguistic and cultural terms: the Kabyles, one of North Africa’s Amazigh peoples. The Movement for Self-determination of Kabylia (MAK) advocates the independence of a Kabyle secular republic from Algeria, a state it accuse of violating human rights, attacking Kabylia’s Amazigh personality by imposing a Arab-Islamic identity, and marginalizing its territory. In 2010, MAK created the Kabyle Government in Exile. Every year, the party mobilizes tens of thousands in self-determination demonstrations.

Casamance

Lying in southern Senegal, Casamance is almost cut from the rest of the country by Gambia. The Casamance movement began to organize itself during the French colonial era, but it was not until the 1980s that it launched a political and armed struggle for independence, when the Movement of Democratic Forces of the Casamance (MFDC) was established. The group, later on, suffered several internal divisions, while at the same time a huge social rejection against the military conflict emerged. Under the auspices of the Community of Sant’Egidio, peace talks —still ongoing— were launched between Senegal and the MFDC in 2012. The Senegalese government has promised economic development in Casamance and a decentralization plan for Senegal as a whole.

Ogaden

East Ethiopia is a dry and impoverished area, almost exclusively populated by Somalis, who on paper enjoy self-government under the Ethiopian federal system but that are effectively ruled by the central state. Some 40% to 70% of Ethiopia’s Somalis, depending on sources, are members of the Ogadeni clan, among which the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) has its main support base. The ONLF is a politico-military group established in 1984 during the dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam aimed at achieving Ogaden self-determination —including an option for independence. After Mengistu was overthrown, the ONLF won in 1992 the election for the newly-established Assembly of the Somali Region, with 60% of the seats. The party sought to start a self-determination process, but the Ethiopian government prevented it from doing do and pushed the ONLF out of power. The group then went underground. In 2007 it launched a violent escalation, which was answered by the Ethiopian army with repression and murder of civilians. Since 2012 peace talks between the ONLF and the Ethiopian government, under Kenyan facilitation, have been ongoing.

Oromia

The south of Ethiopia is populated by dozens of different peoples, the largest of which is by far the Oromo people. The Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) was born in the 1970s to seek an end to what Oromo nationalism says is the colonial-like yoke of central and northern Ethiopians —the Amharas and the Tigrayans. Some sectors of the Oromo national movement want the establishment of an independent Oromo republic while others seek a democratic reform that gives the Oromo people a genuine measure of self-government inside Ethiopia. In the last years, the OLF has carried out several attacks against the Ethiopian police and armed forces, which have coincided in time with Oromo civil society protests against authoritarianism, corruption and territorial expansion of Addis Ababa at the expense of Oromo land.

Azawad

The rise of the Independent State of the Azawad in 2012 in the north of Mali was as glaring as its demise. In January, MNLA forces (a mainly Tuareg politico-military group) launched a campaign that allowed it to control more than 700,000 square kilometers. In April, the group proclaimed independence, not being recognized by any country. In June, in just three days, the MNLA lost control of all north Mali’s major cities at the hands of an armed Islamist coalition, independent Azawad ceasing to exist in practice. The 2012 events meant one more milestone for the Malian Tuareg movement, which has since the 1960s tried to achieve either autonomous status or full sovereignty. Such political goals are echoed by their ethnic kin in neighbouring Niger.

An emerging crisis? The case of Kenya

Until recently, Kenya had found itself largely free from secessionist tensions, exception made for some Somali irredentist demands in the east. Things, however, could be changing. Calls from the Mombasa Republican Council for the establishment of a coastal independent state emerged in 2012. The demand has not completely ceased, and as a result of the 2017 presidential election crisis, two coastal governors have put the idea back on the table. It is not the only debate on independence that has emerged from the electoral conflict: governors and MPs opposing president Uhuru Kenyatta have proposed the partition of Kenya into two countries, and have filed a bill to make it effective. Under that scheme, western and coastal regions —the areas that turned their backs on Kenyatta— would secede from Kenya’s central lands. The demand might be temporary, but it is also true that it has become part of the Kenyan political debate.