Dossier

Indigenous and Afro-descendant women’s years-long struggle for their rights in Nicaragua’s South Caribbean Coast

Collective organization, education and empowerment are some of the means used to reverse rights violations · Afro-descendant and Indigenous peoples denounce that semi-autonomy of coastal peoples is far from being substantial

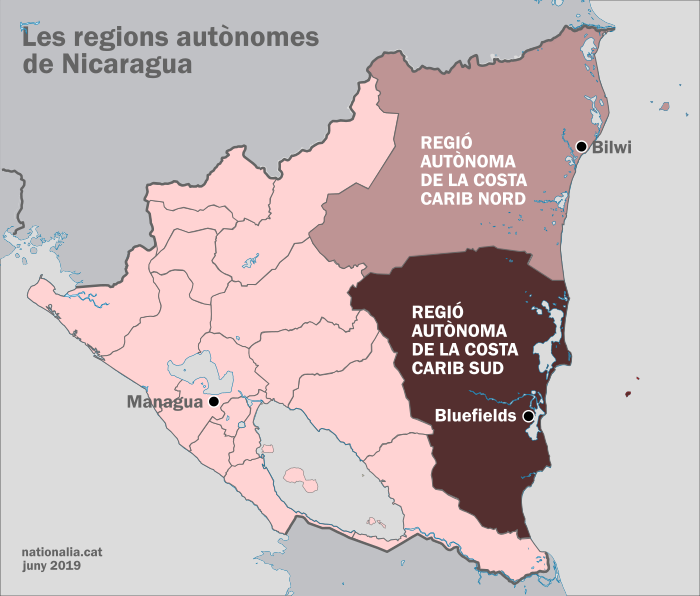

There are seven different peoples living in the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region: Creole, Miskito, Garifuna, Ulwa, Rama, Sumo and Mestizo, the latter being the predominant one. Afro-descendant peoples —Creoles and Garifunas— and Indigenous peoples —Miskitos, Ulwas, Ramas and Sumos— are found throughout different municipalities of the RACCS, mainly in Laguna de Perlas, Desembocadura de Río Grande, Corn Island and Bluefields.

Cultural convergence makes Nicaragua’s South Caribbean Coast a rich area in terms of history, culture and tourism, where different peoples live together with their differences. In turn, they seek to preserve their origins, since, with the globalization and transculturization, there has grown a fear that those groups might lose their essence: they struggle to continue passing all their unique features on to the new generations.

Enactment of the Autonomy Law

The autonomy for Nicaragua’s Caribbean Autonomous Regions (North and South) was a great challenge. For many years, coastal peoples —or Costeños— had been fighting for decentralization, given the fact that many local specificities —peoples living there, their culture, languages or customs— diverged from the rest of the country. The Political Constitution of Nicaragua states that “the communities of the Caribbean Coast are indivisible parts of the Nicaraguan people, and as such, they enjoy the same rights and have the same obligations. These communities have the right to preserve and develop their cultural identities within national unity, to provide themselves with their own forms of social organization, and to administer their local affairs according to their traditions. The State recognizes the communal forms of land ownership of the communities of the Caribbean Coast, as well as the use of and benefit from the waters and forests of their communal lands”.

Map of the Autonomous Regions of Nicaragua —North and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Regions

It was not until 1987 that the statutes of what would become the new Law 28 (Law of Autonomy) were drafted, which solely applies to the two Caribbean regions. This meant a recognition to the Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations, where the native inhabitants would have the option of choosing their own regional authorities by secret ballot, in which the candidates were required to hail from the North and South Caribbean. The process of electing members of regional parliaments began in 1990, with 45 members for each region, and over 4-year periods. Later in 2017 an extension of one more year per term was introduced.

Another power granted to the Autonomous Regions by the Law 28 is the management of their assets, their financial resources provided by the State, and other financial resources obtained from national or international revenues. The wording of the law makes it clear that the inhabitants of the Caribbean Coast have the right to live and develop under the social organization forms that correspond to the peoples living there.

It was expected, with the Law of Autonomy, that there would be a certain independence of the North and South Caribbean Coast, in which decisions were to be taken without any type of interference by the central government.

But in reality, autonomy has largely been ignored, since regional authorities follow the guidelines given by the parties they represent, not the desire of their voters. All of this, over time, has created a disillusionment to the point that many Costeños no longer believe in autonomy.

Afro-descendant women feel discriminated against

Sasha Castillo Ordoñez, an Afro-descendant woman from the South Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua, is a native of Laguna de Perlas. During the last 10 years she worked in various civil society organizations on the matters of education and human rights of women, and human rights in general. Presently, she thinks that there are many difficulties in working for human rights due to the persecution by the government in power, since the rulers consider any group of people gathered to promote certain subjects as suspicious. That is why the organizations have been disintegrating one by one —including feminist groups. In case of black and Indigenous women, Castillo says that there is more discrimination, racism and inequality: “Even though it is said in the presidential speech that we live in equality, the reality is different,” the feminist leader remarks.

Castillo says that “black and Indigenous women are not visible in work places. There are very few women who can have access to jobs. The majority of the people who can get a job are men, even within the Mestizo population”. Regarding the functioning of the autonomy, “unfortunately, regional governments do not defend the rights of the peoples of the Caribbean, insomuch that neither they comply with the provisions of the Law of Autonomy. On the contrary, they have contributed to ending the natural and marine resources of Afro-descendant and Indigenous territories. They only obey partisan directions”.

The feminist leader adds that the black organizations are currently disintegrated, but back in the day she was a member of the Organization of Afro-Descendant Women in Nicaragua (OMAN, Spanish acronym), working on a “multi-ethnic women’s agenda”, which, at that time, was presented to the Regional Council for this agency to implement their demands within its governance policies. The proposal had no results, as it was brought to a standstill —like many other proposals that do not receive the importance they should have—, given that regional authorities belittle the issue of women’s rights.

For her part, Dolene Miller has been immersed in social issues since her youth. A psychologist by profession, she takes interest in human rights, civic education and citizen participation, and currently she works with the Afro-descendant Women’s Network. “The Afro-population was recognized in the Political Constitution of Nicaragua until 2014,” she points out, “but [even then] minority populations did not really have the same opportunities, so they have always had to vociferously defend their rights. Some people, though not usually, have had opportunities to hold significant positions, however this is not enough at the collective level. And, it is even more difficult for black women, because there are less study opportunities for us: black women have not achieved to be very visible in politics. In spite of the fact that, and contrarily, we see them teaching classes, as medical nurses or lawyers in the social field [...] we do not see them in jobs that are considered strong: black women, according to the prevailing sexist culture, must be committed to raising children and to marriage,” she emphasizes.

The human rights defender explains that, in order to reverse the effects of discrimination against black women, the Network always highlights the fact that they are individuals with rights and they are aware that society must change, it has to overcome these sexist barriers and the patriarchy in which they have been educated, and raise awareness about these rights. Regarding the work developed by the Regional Councils, the feminist activist mentions that there are many shady political deals that degrade the rights of the minority peoples, and she denounces that the autonomy process remains halted and there is no development as such: for this purpose, she says, regional political parties were eliminated, keeping only the national ones, thus violating the provisions of Law 28.

Dolene Miller accompanied by other defenders of rights.

Dolene Miller accompanied by other defenders of rights.Miller stresses that the relationship between Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples and the social movements of the rest of the country had certain benefits, for example “when they worked on the issues of rights of women, children, and prevention of violence... Though, there has not been a strong impact. Regarding the cultural and linguistic aspect, we the Creoles do not have problems since we have always maintained the roots that characterize us; however, in the current context of the country, Afro women are afraid to express their feelings, because the society blames you for thinking differently. So it is easier to say nothing and not to face criticism,” she concludes.

Jennifer Brown, a black activist, is the co-founder of OMAN, founded in 2006 and based in Bluefields, the capital of the South Caribbean Coast. The organization conducts training programs for women in black communities, such as Monkey Point, Laguna de Perlas, and in some neighbourhoods of Bluefields. OMAN is the only organization of black women in the entire Caribbean of Nicaragua: Currently it pursues the cases of violence against women, and offers consulting on the issue. One of its main activities is the commemoration of July 25th, International Afro-descendant Women’s Day. “Black women take more part in the Church,” Brown explains. “It has been a challenge for us to achieve that they participate in other decision-making places and in training activities. For us, being a woman and black is a big struggle: due to the context in which we live, due to discrimination, violence, inequality and the stereotypes of black women, like we are hot in bed, or that we must know how to dance... We bear all of this, and for that reason we have worked through the organizations to educate black women, so that they know their rights and stop discrimination”.

“On the political issue,” Brown continues, “the black territory has not received any benefits from the Regional Councils, since they are ineffective. Regarding their functions, they have not created a single public policy or development program for the benefit of black peoples in general. There is no defence for the rights of the Costeñas: regional politicians defend their own interests, not those of the collectives. The fact that the Creole territory has not been demarcated is a proof of it; that is to say, we have not received the ownership qualifications of the communal lands which belong to the Creole people, the lands that the State should be the guarantor of protecting and should not let them be invaded by outsiders. On the other hand, thanks to OMAN and its coordination with the Afro-Latin-American, Afro-Caribbean and Diaspora Women's Network, we work on the policies about women’s rights. Now we have a political platform that works on the issues of justice, development and inclusion, and also, we work with the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (CENIDH, Spanish acronym). These connections have been useful for us to be included in the agendas of these organizations but not in a national policy, for not being inclusive by means of the State,” Brown states.

Indigenous women are not that visible in the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua

Rama Cay Island is located at the south of Bluefields, at the South Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. There lives a very small population of Rama people (1,600 inhabitants, 50% women). Their language, Rama, suffered a transformation with the arrival of the Moravian Church —an old Protestant denomination—, and since then the people adopted a Creole language, which caused a loss of identity.

Antonia McCoy is an Indigenous Rama woman with more than 20 years of work in the Center for Studies and Information on Multiethnic Women (CEIMM) of the University of the Autonomous Regions of the Nicaraguan Caribbean Coast (URACCAN). In the Center they tackle various subjects, such as intercultural perspective of gender, and they have managed to empower many women in aspects related to the forms of violence against women, offering diplomas, courses and workshops addressed to Indigenous women.

McCoy argues that “discrimination has existed since ancient times and it is one of the things that can hardly be eradicated”. Even so, “over the years, we have had a lot of wins regarding the recognition of women’s rights; but inequality persists and we are the most vulnerable for being women, poor and, in addition, from an ethnic group. We, the Rama women, have different characteristics, such as language, traditions and customs; and when we come to the city we have to work very hard to adapt to the majority population, the Mestizos”. She explains that it has been many years that the Association of Indigenous Rama Women (AMIR) exists, “where Indigenous women are trained in various subjects that make them stronger in order to reverse the effects of discrimination, violence and inequality, and to create spaces where Indigenous women can actively participate. The CEIMM, for its part, grants scholarships for conducting research on Indigenous territories focusing on discrimination, violence and human rights of Indigenous women,” she remarks.

The CEIMM has great alliances, such as the Women’s Network Against Violence, the Gender Board, and various universities. Thanks to these efforts, they achieved that their lobbying with the Regional Government in the South Caribbean Coast had a result, through the approval and formation of a Secretary of Women, which was incorporated by women from different ethnic groups of the region. The purpose was to look out for the situation of women, specially regarding the prevention of violence, in which the State would assume this responsibility for women, and by means of a regional public policy. A house-hostel was also created with the support of Andalusian cooperation. After a few years, these two organizations do not work with the same magnitude. Rama women do not have institutional spaces, and McCoy explains that those who have had the opportunity to access public, political and decision-making positions are limited.

Celebration of the 9th of August, the Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Celebration of the 9th of August, the Indigenous Peoples’ DayAnother one of the peoples of Nicaragua’s South Caribbean Coast is the Ulwa people. This ethnic group lives in the Karawala community, with a population of 4,500 people. Ulwa People’s Day is celebrated on May 6th, and the 166th anniversary of their presence at Karawala is commemorated in 2019. One of the main difficulties of the collective is the disappearance of the Ulwa language, since adults no longer speak Miskito, and therefore children do not learn to speak their native language.

Hayde Baptista Salazar is an Ulwa leader. When she was young, she began to train the youth of her church. Later, she dedicated herself to teaching, and in 2008 she undertook a commitment with the Indigenous communities in the territory of the Unity of the Children of Mother Earth (Awaltara), where she promoted equality of women’s participation, to the point that she herself achieved to be the president of this territorial government, a great step towards the inclusion of women.

In 2014, Hayde Baptista was elected as regional councillor, holding a seat at the Regional Parliament: “I gained many experiences there. I wanted to do a lot of things for my community and for women, but unfortunately it was not this way. Because we know that the Autonomous Regional Council¡s only autonomy is in its name: it is dominated by Managua, there is no decentralization, and there is a lot to do [in order] to be able to do something for our autonomy. We need our communities to be empowered. We need Indigenous women to prepare themselves in leadership and in academic sphere, because we are capable of carrying out any position and profession. As regards jobs, we notice a lot of discrimination since doors are not open for us to acquire work, especially in the current context, where, due to political reasons, they do not give you a place simply because you do not think the same way as the government in power. And this is a violation of human rights against Indigenous peoples,” she declares.

The Miskito people, on the other hand, are based in the municipalities of Bluefields, Desembocadura de Rio Grande and Corn Island. On August 9, they commemorate the International Day of Indigenous Peoples.

Laura Padilla is an Indigenous journalist and professor who, through her informative radio program, promotes equality between peoples and the rights of Indigenous women, as she says that they usually live in a situation of dependence on their husbands. “There are very few women who manage to prepare themselves,” she explains, “and if they achieve a college degree, then they have problems choosing a job in their profession. And all of this is because they are women and Indigenous,” she states.

Since 1985, Padilla has been airing the only Miskito program that would allow its countrypeople to understand important news and issues that she addresses. She considers that, through her program, she has contributed to making changes in attitudes within her people, which she values as positive, since the women, she explains, are more empowered and they struggle to gain space in the society, which usually is difficult given the lack of importance that the government gives to the minoritised peoples.

(Translated from Catalan language by CollectivaT.)

With support from: