Dossier

The Amazigh: Libya’s third actor?

Amid increasing violence between two rival factions, the country’s biggest indigenous people get set for an uncertain future

“It wasn’t by chance that Gaddafi chose this place to launch a campaign of utter assimilation of non-Arab Libyans,” Ben Khalifa told this reporter from his office last November. His native town is the country’s single Amazigh enclave on its endless coast. It borders Tunisia to the west, the predominantly Arab city of Sabratha to the east —a former ISIS stronghold—, and it is surrounded by a cluster of Arab villages where Gaddafi loyalists were once strong: Zuwara is very much an island in its full sense.

“Logistics are usually tricky here. One has to plan carefully before taking the road either to Tripoli or to the mountains to avoid undesired surprises,” noted the political leader.

Also called “Berbers,” the Amazigh are indigenous inhabitants of North Africa, with a population extending from Morocco’s Atlantic coast to the west bank of the Nile in Egypt. Unofficial estimates put the number of Amazigh in Libya at almost 600,000, or about 10 percent of the country’s total population. During Gaddafi’s “cultural revolution,” any publications not in accordance with the principles espoused in his Green Book were destroyed, including those mentioning the Amazigh. According to Libya’s former leader, this indigenous group was of “Arab origin” and their language “a mere dialect”. Registration of non-Arab names was forbidden, Libya’s first Amazigh organization was banned, and anyone involved in their cultural revival was prosecuted. Ben Khalifa lived in Morocco for 16 years until he left for the Netherlands to escape pressure from Gaddafi on Rabat to hand him over. He resumed his dissident activities from Tunisia when the uprising started in Libya. Gaddafi was finally toppled in 2011, but changes wouldn’t be as smooth as expected. As the only Amazigh member of the National Transition Council —the parallel government set up back then by the opposition—, Ben Khalifa says he saw “little differences” between his partners and the ousted ruler.

“They had the same old mentality rooted in Arab nationalism and Islamism so we saw little will to grant the rights of non-Arab Libyans. By the time Tripoli fell in the hands of the rebels we had already broken relations with them,” said Ben Khalifa, before he produced a leaflet of his political party written in the Tamazight, Arabic and Tebu languages.

“In a way, we need to re-educate fellow Libyans, we need to remind them that ours is not an Arab country but a North African one. Our links with both shores of the Mediterranean are way stronger than those with the Gulf countries,” stressed the political leader. It won’t happen tomorrow. LIBO was set up in 2017 to run for elections originally scheduled in 2018, but which never took place. In fact, Libya has remained divided and lawless since 2011, and two rival governments vie for power since 2014. Amid this chaos, the warlord of the eastern part of the country, general Khalifa Haftar, launched an offensive on Tripoli in early April. According to the World Health Organisation, more than 400 fighters and civilians have been killed in Tripoli so far, with over 6,000 people wounded and more than 50,000 residents forced to flee their homes in the suburbs.

Ben Khalifa points to the worst episode of violence in years. “Who could possibly expect such a move? He says over the phone. “What is more, what’s the plan, if any, for the country?”.

Language and gender

Despite the unresolved and seemingly endemic political conundrum in Libya, the Amazigh community has tried to fill the vacuum of four decades of neglect of their language and culture. It wasn’t until Gaddafi lost control over Libya that the first schools and publications in Tamazight popped up across Amazigh villages. Over the last years, Amazigh school books have gradually been released and Tamazight has become a language taught at primary schools, and even universities. The campus in Zuwara hosts a Tamazight department. Set in 2017, it had to rely on Tamazight teachers from Morocco and Algeria at the beginning, but Nafaa Malti, head of the department, is convinced that today’s local students will be tomorrow’s teachers here.

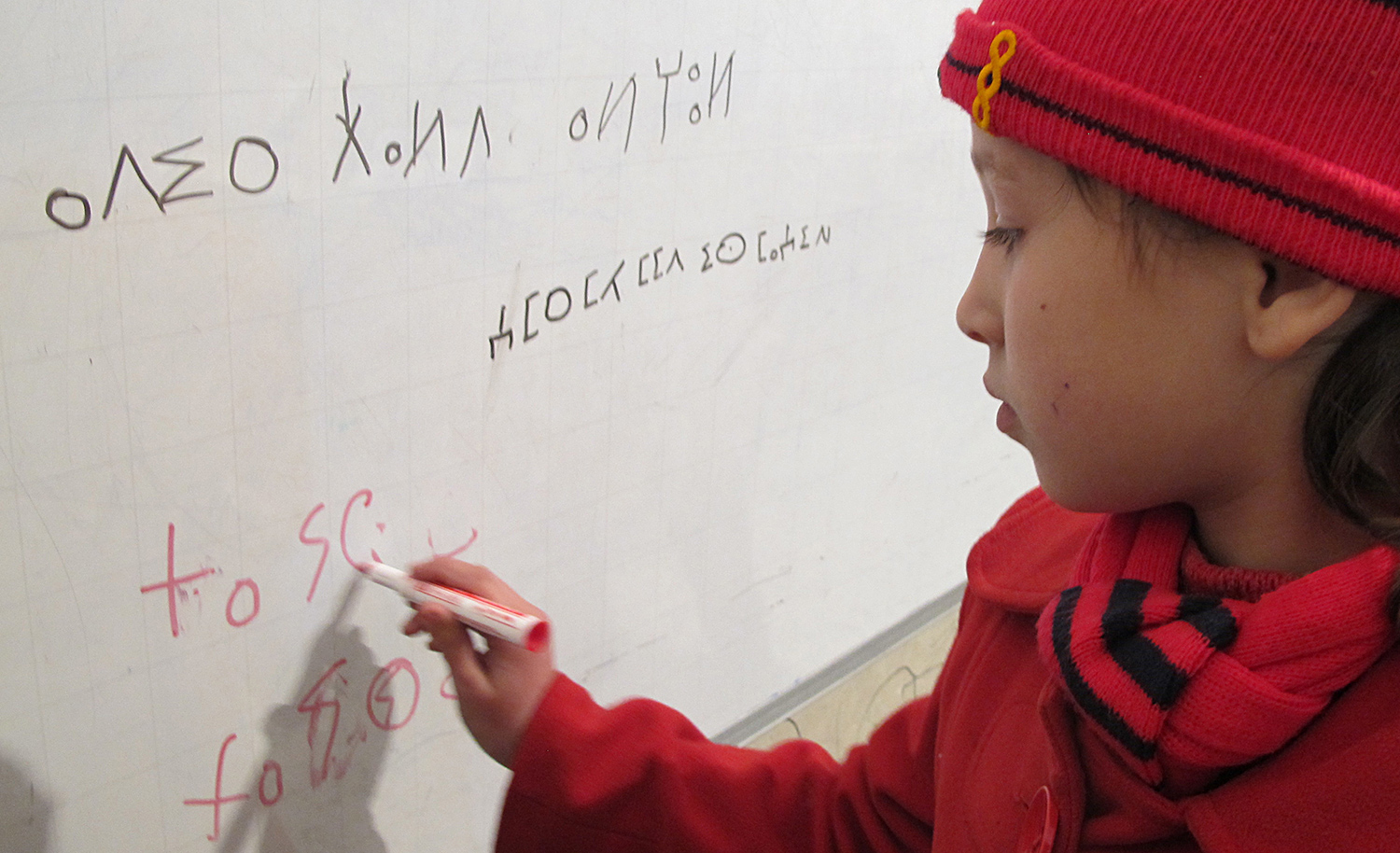

A Tamazight lesson in Jadu, Nafsa mountains. / Image: K. Z.

A Tamazight lesson in Jadu, Nafsa mountains. / Image: K. Z.“The rest of the country is too busy in fighting each other. Nobody seems to understand the importance of education, but we do,” said the academic. The newly set studies are doubtless a visible achievement, but which owes its success to the high number of volunteers who have been working against the clock to make up for lost time after four decades of systematic neglect. The majority of them had Tamazight as their mother tongue, but it was not until 2011 that they started to use their own alphabet too. They call it Tifinagh, and it was forbidden during Gaddafi’s time.

“The only way to learn how to read and write during Gaddafi was through the Internet. That’s how we all taught it to ourselves,” recalled Nuha al Hassi, a 29 year old volunteer from Zuwara who is a key figure in the field of education as well as staunch activist for the rights of women. According to her, separating politics from religion is “key to solve many of the country’s current problems.” Sitting next to her, Fatma al Omrani, co-founder of the Tamazight Women’s Movement (TWM), nodded. She expected “much more” from the 2011 uprising.

“I thought women would have a bigger role in post-Gaddafi Libya and I also expected full rights for us. Unfortunately, it’s not the case as religion is always used against us in courts and all aspects of life,” said the 29-year old activist from Zuwara.

Asma Khalifa, also a co-founder of the Tamazight Women’s Movement says it is getting increasingly difficult and dangerous for women as Salafists take over the political structures. Apparently, it is not just about religion. “Men simply don’t want to see us even in the streets,” Khalifa said by phone. In early May, Inas Miloud, also a member of TWM, spoke before the UN Security Council in New York on a panel about sexual violence where she labelled “full participation of women in public life” as an “essential step forward” yet to be taken. Moreover, the activist also accused the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) of excluding Libyan women and indigenous groups.

“Hundreds of indigenous women are targets of sexual and gender-based violence simply because they belong to communities such as the Tebu, the Tuareg and my own people,” denounced Miloud in the same speech. In 2018, Libya was ranked 11th in a list of countries with “peoples under threat”, just behind Myanmar, according to NGO Minority Rights Group International. Syria topped the list.

“Misguided and aberrant”

Adhering to a different version of Islam other than Libya’s official one also adds to the long list of problems for many Amazighs. Whereas most Libyans belong to the Sunni Maliki tradition, a small number of Ibadi Muslims also reside in the country. Neither Shia nor Sunni, and for the most part not even Arab, Libyan Ibadis are currently working to restore a branch of Islam that is said to have been founded before the Shia/Sunni schism, but which was largely marginalized under Gaddafi. Libya’s former leader saw in Ibadism yet another sign of the national identity which did not match his own narrative.

Other than in Libya, there are also pockets of them in the Mzab valley of Algeria, the island of Djerba in Tunisia, and on the Swahili coast, just below the Horn of Africa. In Zuwara they gather at the Abdurrahman Elouali Association of Ibadi Studies, also in the main square. Several among its members claim to have been jailed during Gaddafi’s times, but prosecution is seemingly not over. In August 2018, Libya’s Supreme Fatwa Committee —the religious arm of the country’s eastern government—, released a fatwa which labelled Ibadis as “a misguided and aberrant group” and “infidels without dignity.”

“The fatwa was actually more political than religious but we got support from several intellectuals as well as senior Sunni leaders so it has actually been a positive thing for us,” claimed Sheikh Issa Nobar from the organization’s library. Similar entities can be found in the Nafusa mountains, where there is literally no Amazigh village without a mosque where locals can practice their faith. In villages like Nalut, the biggest in the mountain range, there is a library full of Ibadi volumes and manuscripts, and even Libya’s only Ibadi school.

The view over the valley from the Nafusa mountains. / Image: K. Z.

The view over the valley from the Nafusa mountains. / Image: K. Z.Valerie Hoffman, professor of Islamic studies at the University of Illinois and an expert on the Ibadi community, points to one contradictory yet positive duality.

“In theory, we could say Ibadism is a rigorist and conservative vision of Islam, but in practice they have historically been very tolerant. Any hostile action is reserved for one type of person: the unjust ruler who refuses to mend his ways or relinquish his power,” the academic told Nationalia on a phone conversation.

“It doesn’t matter who is in power down the valley,” reflected Ali Flifel, the headmaster of the Nalut’s Ibadi high school. “We are neither Arab nor Sunni, so we know we are pretty much by ourselves in Libya.”

Territory

For the time being, the besieged city of Tripoli still hosts the UN recognized government, and it is also where the Amazigh Supreme Council (ASC) has its headquarters. The ASC is the umbrella organization for the ten main Amazigh locations in Libya, with representatives chosen in groups of three: a delegate of the municipal council as well as two other candidates —male and female— elected by each town. It held its first congress in September 2013, agreeing on a clear demand for the constitutional recognition of their language. That was also when the organizers decided to create representative bodies for each of the Amazigh towns in Libya. The one in Zuwara was elected in November 2011, in which was actually Libya’s first ever democratic election. Over the years, the council has been holding monthly meetings in their Tripoli headquarters, or as often as security conditions allow.

Unsurprisingly, it is getting increasingly difficult since the offensive was launched over Tripoli. In a press release —in Tamazight, Arabic, and English— dated April 17, the ASC condemned the shelling of Tripoli by Haftar’s “criminal militia” while calling on the GNA, the UNSMIL and other international bodies “to assume their responsibilities to protect civilians and apprehend the perpetrators.”

The Amazighs’ rejection of the eastern Libya’s warlord is crystal clear, but that does not imply they fully align with Tripoli’s UN-backed executive. Accordingly, the Amazigh armed militias remain in a defensive position and not actively taking part in the fight against Haftar.

“We have achieved our independence de facto because on the governmental and legislative levels under the GNA we gained none of our rights,” Seham Bentalab, an elected ASC member active in both the Education and the Foreign Relations departments, told Nationalia over the phone. According to this lawyer from the Nafusa mountains who speaks on behalf of the ASC, a solution for Libya would be a decentralized administration where the Amazigh would have an autonomous region of their own. It would stretch from Zuwara all the way down to Ubari bordering Tunisia and Algeria. Bentalab said the eastern boundary with Arab Libya is yet to be agreed. The question of autonomy is far from being a post-Gaddafi trend. Back in 2006, Mazigh Buzakhar, a well known Amazigh activist who would also be imprisoned alongside his twin brother Madghis, came up with a draft paper which circulated through an underground network. The so-called Autonomy, the concept and the establishment of the Movement for an Autonomous Region in Nafusa was an early attempt to import the ideas of the Algerian Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylia (MAK). Founded in 2001, the MAK seeks autonomous rule in Kabylia, a region of northern Algeria populated by an Amazigh ethnic group.

When asked about more recent precedents, Bentalab was blunt:

“The Kurdish experience in Syria is a source of inspiration for us. It also comes to confirm that there is no other solution than enjoying real sovereignty over your land to achieve your rights.”

.